In this country we call this day Veterans’ Day and take time to honor all those who have served or are serving in our armed forces. It was originally called Armistice Day which commemorated the cessation of fighting on the Western Front of World War I, which took effect at eleven o’clock in the morning—the …

Tag: World War I

Nov 11 2021

Armistice Day 11/11/21

In this country we call this day Veterans’ Day and take time to honor all those who have served or are serving in our armed forces. It was originally called Armistice Day which commemorated the cessation of fighting on the Western Front of World War I, which took effect at eleven o’clock in the morning—the …

Nov 11 2020

Armistice Day 11/11/20

In this country we call this day Veterans’ Day and take time to honor all those who have served or are serving in our armed forces. It was originally called Armistice Day which commemorated the cessation of fighting on the Western Front of World War I, which took effect at eleven o’clock in the morning—the …

Jun 09 2014

A-C Meetup: Part 1 on the Need for Anti-Capitalist Democratic Internationalism by Galtisalie

[Note: This is my version of light summer reading (but my nickname’s not “Buzzkill” for nothing). Hey, I’m even breaking this diary into two parts. It’s not healthy to read while you eat but if you do, have a nice sandwich (better make that two), chew slowly, and by the time you’re to the pickle, maybe you’ll be done. I want to present in bite-size easily digestible pizzas my vision of a peaceful deep democratic revolution. I’m not there yet. I enjoy all the rabbit trails that make up the whole too much and mixing metaphors like a … concrete mixer. (Do similes count?–see, I do know the difference.) Below all bad writing is my own and unintentional.]

No pressure, but in late 2012 Kyle Thompson at The other Spiral wrote:

I think the most important thing at this point in time is for the left to reclaim three areas: 1) Internationalism 2) The vision of the future and 3) Economic legitimacy. Without internationalism each struggle feels isolated and localism will never be anything more than localism. … Similarly the left needs to reclaim the future. If all we can imagine for the future is dystopia we will never be motivated enough to build socialism. This is basically the work of artists, conjuring up an image of what might be …. Finally the left must fight to achieve at least a niche of respectability in economic discourse.

I’ll up the ante and say that together we must constantly work to combine all three into a new praxis, one that learns from the past but also is willing to modify or even Jetson imagery that unnecessarily divides us. But, we’ve caught a break: in case you haven’t noticed, a lot of capitalist imagery has worn thin. Ecology and unemployment are biting capitalism on the buttock, just as our side predicted. When I was a kid, I was counting on one of those glass-topped space sedans to zip me around town one day. I’m beginning to doubt that’s going to happen. The caution yellow Pinto with shag carpeting on the dash that zipped me to my first job has long since finished rusting to nothingness, and only the bondo I liberally applied during those bong-heady times remains at the bottom of some landfill.

The future is with us, and that’s scaring the bondo out of the oligarchy, but our side’s still dazed and confused, and the oligarchy wants to keep its party going until the polar ice cap has gone and every last carbon chain has been broken to fuel the Pintos of the 21st century we will purchase to drive to the jobs we won’t have. I’m no artist and have no credentials for economic discourse. That leaves me with a possible niche of utility if not respectability researching internationalism. But since I’m writing from the Deep South of the U.S., home of a widely-held theory about the U.N. involving the mark of the Beast, I’d better toss in some revolutionary ever-modern art to get things started, and, in Part 2, follow-up with Luxemburg, who gives the political-economic basis for anti-capitalist democratic internationalism. If Rosa’s not respectable and respectful enough for the dismal scientists they can kiss my grits.

When El Lissitzsky created “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge” he made a conscious decision to use the forms of the unrepresentational feelings-based supremacist school he had helped found to focus on their artistic opposite: the material world as he perceived it. This professional betrayal was motivated by a higher duty: universal morality. As a Russian Jew who’d lived most of his life under the Czar’s antisemitism, he wanted to use the best tools that he could muster to help beat the reactionary White Army. Nothing could have been more literal in the minds of the populace who viewed the poster and others like it in the Russian Civil War. Yet the use of geometric shapes and a limited palette brings a discordant transcendence so that even now when one looks at the poster it appears relevant– or so would have said two kids I showed it to if they used big words. Subconsciously, it is up to the individual viewer to decide where he or she fits among the objects, while pining for something missing from this divided two-dimensional incomplete but sadly accurate plane.

What tools do we have to muster and for whose cause should we be mustering them? Key questions of the 20th century and always.

I write this on the 70th anniversary of D-Day, when humanity did not need national banners to know that Hitler’s eliminationist ethnic nationalism was so inhumane it had to be defeated. (But humane posters are always useful.) Capital “F” Fascism has a way of reemerging on our one planet, and we rarely on this day consider why that is in our justifiable remembrance of the lives that were lost on those bloodied shores of Normandy. I am sure that millions of D-Day-themed posts and comments in blogs and on Facebook pages will be published before this one comes out on Sunday night, June 8, 2014. Rather than add to the digital pile, I am instead going to focus on the war to end all wars that came one generation before WWII, the choices that are involved in warring, and the political-economic reasons we keep doing the wrong thing as a single human species.

Interesting, “national” banners. They pop up, as with the U.S. Civil War, before ethnic armies that are not even nations. Two passed me night before last as I was walking my dogs in the Deep South: the rebel flag flying proudly on the right of the back of an old imported pick-up truck with its windows down driven by a “white” man with the Libertarian “Don’t Tread on Me” flag on the left. The skinny bearded great American working class Confederate man calmly smiled and nodded at me inclusively, assuming I was part of his team, like we were about to go over together and kick the dead Yankee bodies at Bull Run just for grins, or perhaps attend a lynching and pass the bottle (not spin the bottle mind you, 100% virile straight man fun stuff). I was wondering if he heard my loud “Booooo,” particularly when he began to slow down about thirty yards past me. (At least I thought it was loud, but not so loud as to upset the dogs–but pretty darn loud people.) I thought he, likely packing, was turning around to come back and tread on me or worse, but he turned right, fittingly. Maybe he had second thoughts about murder or maybe it was his muffler problem that allows me to write these words. How do we get him out of the white circle and in the natural polychromatic sphere of life, not pictured here? I think he’s hopeless, so mostly I ignore him, but, if and when he waves his hateful flags in my neighborhood or yours, I propose confrontation, red wedge wielded. And somewhere, those flags are always waving. And innocent kids are being raised to be in the white circle.

Dec 13 2009

On The Futility Of War, Part One, Or, Snow Becomes A Lethal Weapon

We have another one of those “amazing history” stories for you today-and this one’s a real doozy.

We’re going to spend the better part of four years in the Italian Alps (or, to be more accurate, what was intended to be the Italian Alps), and by the time we’re done, nearly 400,000 soldiers will have been killed-and 60,000 of those will have died as a result of avalanches that were set by one side or the other.

In the middle of the story: a mountaineer and soldier who was so highly regarded that even those who fought against him accorded him the highest honors they could muster, creating a legend that lives on to this very day.

And even though a young Captain Erwin Rommel fought in these battles…it’s not him.

Oh, by the way: did I mention that there are also some handy object lessons for anyone who might be thinking about fighting a war in Afghanistan?

Well, there are, Gentle Reader, so follow along, and let’s all learn something today.

Nov 11 2009

War, Paradox, Personality, and the American Mindset

This holiday, which denotes the eleventh day of the eleventh month was once called Armistice Day, as it marked the end of hostilities during World War I. It is unfortunate, in my opinion, that our collective memory of that conflict grows fainter and fainter with each passing year, since it marked the exact instant we grew from a second-tier promising newcomer on the world stage to a heavy hitter. The European continent had threatened to blow itself up for centuries before then, but with a combination of ultra-nationalism and mechanized slaughter, millions upon millions of people perished in open combat. Our entrance into the war and world theater turned the tide but the original zeal that characterized the war’s outset had become a kind of demoralizing weariness that our fresh troops and tools of the trade exploited to win a resounding victory. Our industries revived Europe, making us wealthy in the process, and though much of this wealth was lost in The Great Depression, precedent had been set. When Europe blew itself apart once more in World War II, their loss was our gain.

A year ago today I was at Mount Vernon, enjoying a day off at George Washington’s home, taking in the iconic and beautiful view of the Potomac river. Along with the steady stream of tourists like myself were servicemen and women from every branch of the Armed Forces. A ceremony at our first President’s tomb commemorating the bravery of all who had served was to be held mid-day and, deciding I’d watch it for a while, I began moving in the direction of the Washington burial plot. What ringed the tomb was often more interesting than the main attraction. Case in point, the burial site of the estate’s slaves, which had been given posthumous mention, though the names, dates of birth, dates of death, and individual stories had long since been lost to posterity. I mused a bit that this was how most Americans living today felt about the Great War.

The scene struck a discordant note with me in another way. It’s the same on-one-hand, but on-the-other-hand kind of conflicting emotional response that underlies my thinking about war and those who engage in it. If I am to follow the teachings of my faith, war is never an option to be considered for even half a second. Indeed, if it were up to me, I’d gladly abolish it from the face of the earth. However, I never want to seem as though I am ungrateful or unappreciative of those who put themselves in one hellish nightmare situation after another as a means of a career and with the ultimate goal to protect us. It is this same discomforting soft shoe tap dance that I take on when I pause to give reverence to the memories of those who established and strengthened our nation, while recognizing too that they were indebted to a practice I consider deplorable.

I would never describe hypocrisy as a kind of necessary element in our society, but a “do as I say, not as I do” quotient that seems to be commonplace in our lives does merit recognition. For example, quite recently a friend of mine who had lived in France for several months was describing to me the cultural differences in attitude towards sex in our culture versus theirs. Here, we are indebted to a hearty Puritanism which shames those who engage and scolds those who make no attempt to conceal. Yet, we still think nothing of eagerly consenting to casual sex and our media and advertising reflect this. As it was explained to me, in France, sex is everywhere, no one feels as though a highly public display is the least bit out of place or vulgar, no one feels guilty at its existence, but they are much less inclined towards hooking up with complete strangers or faintly known acquaintances than we are. It is certainly interesting to contemplate whether we’d sacrifice the right to one-night-stands or the promise of frequent escapades if after doing so we would henceforth face no repercussions of guilt and strident criticism for daring to see sexuality as something more than a weakness of willpower and a deficit of character. One wonders if we would sacrifice achieving something with nearly inevitable consequences attached for the sake of not getting what we want whenever we want it. The trade off, of course, being we would no longer have to feel dirty or ashamed for having base desires.

I mention this paradox in particular because the national past-time these days might be the sport of calling “gotcha”, particularly in politics. The latest philandering politician is revealed for the charlatan he is and our reactions and responses are full of fury and righteous indignation. “How dare he!” Granted, one party does seem to act as though it has a monopoly on conventional morality, but if it were my decision to make, I’d drop that distinction altogether, else it continue to backfire. Yet, this doesn’t mean we ought to take a more European approach, whereby one assumes instantly that politicians will be corrupt and will cheat, so why expect anything otherwise. Still, we ought to take a more realistic approach towards our own flaws and the flaws of our leaders instead of adhering to this standard of exacting perfection which has created many a workaholic and many a sanctimonious personal statement. To the best of my reckoning, we must be either a sadistic or a masochistic society at our core. Perhaps we are both.

It is easy for us to make snap judgments. I have certainly been guilty of it myself. Taken to an extreme, I can easily stretch the pacifist doctrine of the peace church of which I am a member. I can imply that military combat of any sort is such an abomination that everyone who engages in it is beholden to great evil and deserves precisely what he or she gets as a result. This would be an unfair, gratuitous characterization to make. Though I do certainly find war and warfare distasteful, I prefer to couch my critique of the practice in terms of the psychological and emotional impact upon those who serve and in so doing speak with compassion regarding those civilians in non-combat roles who get caught in the middle and have to live with the consequences. Likewise, I would be remiss if I dismissed the role George Washington played in the formation of our Union if I reduced him to an unrepentant slaveholder and member of a planter elite who held down the struggling Virginia yeoman farmer. Moreover, I could denigrate the reputation of Woodrow Wilson, whose leadership led to our victory in the First World War, by pointing to his unapologetic beliefs in white supremacy and segregation. I could mine the lives of almost everyone, my own included, and find something distasteful but somewhere along the line we need to remember that hating the sin does not meant we ought to hate the sinner, too.

The conflict swirling around us at this moment is just as indebted to paradox as the sort which existed during the lives of any of these notable figures in our history. John Meacham wrote,

…[T]he mere fact of political and cultural divisions—however serious and heartfelt the issues separating American from American can be—is not itself a cause for great alarm and lamentation. Such splits in the nation do make public life meaner and less attractive and might, in some circumstances, produce cataclysmic results. But strong Presidential leadership can lift the country above conflict and see it through.

This is what we are all seeking. While I am not disappointed by President Obama, I see a slow, deliberative approach to policy that is alternately thoughtful and exasperating. I certainly appreciate his contemplative, intellectual approach, and can respect it even when I disagree with its application. One of the paradoxical tensions that typify the office of Chief Executive or any leadership role, for that matter, is the balance between power and philosophy. Meacham again writes,

…Politicians generally value power over strict intellectual consistency, which leads a president’s supporters to nod sagely at their leader’s creative flexibility and drives his opponents to sputter furiously about their nemesis’s hypocrisy.

If ever was a national sin, hypocrisy is it. It is the trump card in the decks of many players and it is used so frequently that one can hardly keep track of the latest offender. If it were not everywhere and in everyone, it would not be such a familiar weapon. Even if one has to split-hairs to do it, one can always locate hypocritical statements or behaviors. Politics can often be an exercise in pettiness, and the latest bickering between Republicans, Democratic, liberals, center-left moderates, conservatives, and center-right moderates have morphed into this same counter-productive swamp of finger-pointing. It is this attitude which keeps voters home and leads to further polarization. Securing Democratic seats and a healthy majority in next year’s elections will require rejuvenation of the base but also inspiring moderate and independent voters to even bother to turn out to the polls. What this also means is that we ought to learn how to forgive ourselves for our shortcomings and recognize the humanity in our opponents as well. A scorched-earth strategy works for the short term, but it also guarantees a ferocity in counter-attacks and leads to long-term consequences only visible in hindsight. By all means, fight for what one believes, but eschewing tact and diplomacy is the quickest way to both live by the sword and die by it. I’m not suggesting toughness or steel-spines ought to be discarded, but rather that we all have weaknesses of low hanging fruit that make for an easy target, and the instant we eviscerate our opponent by robbing their trees, we should soon expect a vicious counter-attack in our own arbor.

Jan 30 2009

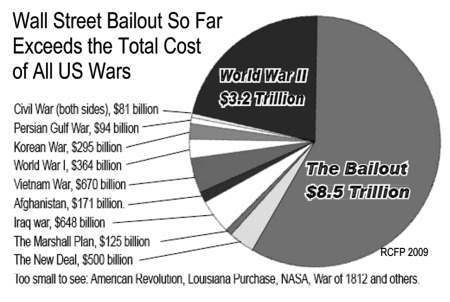

Wall Street Bailout Costs More than US History.

Casey Research, of Vermont, has analyzed the costs of the government bailouts of the housing crisis, the credit crisis and others and has concluded that the total is $8.5 trillion, which is more than the cost of all US wars, the Louisiana Purchase, the New Deal, the Marshall Plan and the NASA Space Program combined. According to CRS, the Congressional Research Service, all major US wars (including such events as the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War, the Spanish American War, World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan, the invasion of Panama, the Kosovo War and numerous other small conflicts), cost a total of $7.5 trillion in inflation-adjusted 2008 dollars.

http://www.rockcreekfreepress….

hat tip to Ilargi.

Jul 22 2008

The Bonus Expeditionary Force

It must have had a dreamlike quality to it: a summer’s day in Washington, the tanks and troops on the street accompanied by officers like George Patton and Dwight Eisenhower, led by none other than General Douglas MacArthur. America’s Caesar was wearing a full salad bowl of ribbons and medals, magnificent astride a great horse; to the impoverished veterans he was riding to meet, he must have looked like a mighty warrior of a bygone era. Then, to their horror, the Chief of Staff of the US Army ordered his infantry to fix bayonets, his cavalry to draw sabers, and his tanks to move forward.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, we’re tonight’s historiorant finds Depression-hit vets of the First World War encamped in a Hooverville in Washington during the summer of 1932. I’m not saying it contains lessons to be learned about the interrelationships of Republican presidents, veterans, economic depression, and violent authoritarianism, but as St. Colbert once said, “I can’t help it if the facts have a liberal bias.”

Mar 21 2008

“Shell Shock”; PTSD, and Executions of Those With!!

The following Video was left as a reply in my Daily KOS posting, yesterday, on Nadia and ‘Veterans Village’.

How far have we come as to what Wars do to those we send to fight them?

We don’t Execute?, but we Still don’t Understand, some Denie, and we Don’t Give The Care Needed!

Societies ‘Love War’, at first, especially Wars of Choice, but Societies only send a small fraction of to engage, than they make them Fight for what it does to them!