Picture this: Thousands of warriors, clad in jaguar skins and the feathers of birds of paradise, armed with atlatls and obsidian-studded clubs, move steadily through a rainforest toward a distant cluster of pyramids and temples. Like every warrior on the eve of every battle in all of human history, they wonder if they will survive the coming fight. Some of them probably think about the circumstances that had brought on the war in which they have found their generation cast, and perhaps a few of them even consider the part they are playing in the greater socio-cultural drama unfolding in northern Guatemala in the 7th century CE.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight’s historiorant centers around those quarrelsome city-states of the Classical Maya. On this Columbus Day (a/k/a 7 Muluc 12 Yax), I invite you to take a break from Republican vileness and winking wannabe-veeps, and join me for a tale of the first Star Wars – a struggle between ancient Mesoamerican superpowers punctuated by some very recognizable story lines and subplots…

Historiorant: This diary was originally published at Daily Kos on May 14, 2006. It was inspired in part by the story behind Meteor Blades’ screen name, and in part by how much I dig the history of this part of the world – my undergrad degree is in Precolombian Mesoamerica, and I’ve traipsed many of the sites described below. I offer it now as an escape from the endless drumbeat of political rancor (as appropriate as that might be), in celebration of the No Columbus Day observations being held at Never In Our Names, and because the original go-round was…um…one of my most poorly attended historiorants of all time.

These Aren’t Your Father’s Maya

There’s a lot of popular mythology about the Maya out there, much of it based on perceptions that haven’t held true for 20 years or more. Whether it comes in the form of reminiscences about side trips from Cancun to Chichen Itza, a Mormon perception perception of the history of prehistoric America, New-Agey reinterpretations of what the Maya might’ve thought, or just some vague, jade-encrusted notion that they were pretty good with numbers – society’s view of these folks probably needs some updating.

A great deal of work has been done in the deciphering of Mayan glyphs – about 85% of them are now readable – and they’ve painted (in bas-relief, even) a fascinating picture of Ancient Mesoamerica. Recent discoveries from fields and methods as varied as anthropology and side-scanning radar have now allowed us to glimpse a world of economic rivalry between mighty city-states, dynastic succession of powerful families, rulers with hundreds of thousands of subjects, and a complex cosmology that involved the highest levels of mathematical thought then known anywhere in the world.

The Maya Tapestry

“Maya” is a broad term describing a number of linguistically linked groups inhabiting a region stretching southward from Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the Yucatan Peninsula, encompassing all or part of the modern nations of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Organization of the different linguistic groups was (and still is) along tribal lines, and the entire region to this day is a patchwork of different Mayan tongues. Indeed, one can still cross vast swaths of ostensibly Spanish-speaking countries and never hear a word spoken in castillano (or any other derivative of Latin, for that matter).

“Maya” is a broad term describing a number of linguistically linked groups inhabiting a region stretching southward from Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the Yucatan Peninsula, encompassing all or part of the modern nations of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Organization of the different linguistic groups was (and still is) along tribal lines, and the entire region to this day is a patchwork of different Mayan tongues. Indeed, one can still cross vast swaths of ostensibly Spanish-speaking countries and never hear a word spoken in castillano (or any other derivative of Latin, for that matter).

The Classic Maya civilization – the one that built most of the cities we know as ruins – waxed and waned between 300 and 900 CE, but there is ample evidence of a Preclassic period that stretches well into the 1st Millennium BCE. Like all peoples of the Mesoamerican culture hearth, the Maya derived inspiration and ideas from the much earlier (and even by Classic Maya times, long-defunct) Olmec civilization, which thrived along the northern shores of the lower Yucatan between 1200 and 400 BCE.

Weird Historical Sidenote: “Olmec” is actually a Nahuatl (Mexica/Aztec) word meaning “Rubber People,” and refers to the contemporaries of the Aztecs who lived in the same area as the original builders of the “Olmec” cities. There is some evidence to indicate that these ancient engineers and astronomers may have called themselves “Tamoachan,” but the truth is, nobody really knows much about them. Ironic, since they appear to the root of every common cultural element between all the later civilizations of Mesoamerica.

The Classic Maya created a thriving urban civilization amidst some of the world’s most city-unfriendly environments. Conservative estimates of the population of the city of Tikal, located in the Peten rainforest in northern Guatemala (and a central actor in the story of the Star Wars), at 50,000; other scenarios postulate a much higher number. Regardless, it’s clear that this one city in the middle of the Central American jungle had greater population than most of the contemporary cities of Europe combined – and the Maya realm was dotted with dozens of such places.

The Classic Maya created a thriving urban civilization amidst some of the world’s most city-unfriendly environments. Conservative estimates of the population of the city of Tikal, located in the Peten rainforest in northern Guatemala (and a central actor in the story of the Star Wars), at 50,000; other scenarios postulate a much higher number. Regardless, it’s clear that this one city in the middle of the Central American jungle had greater population than most of the contemporary cities of Europe combined – and the Maya realm was dotted with dozens of such places.

Their civilization was on the rise as Rome fell, and by the height of the Classic Maya period, Europe had fallen into the deepest throes of what is most charitably called the Early Middle Ages. So it was that:

- in Europe, books were as rare as the people who could read them, and monks spent lifetimes copying a handful of Bibles and creating beautiful calligraphy on animal skins. The Maya developed their complex hieroglyphic alphabet on their own, created libraries of codexes – accordion-folding books with pages made of a thin coat of plaster spread over a fiber mat, then painted – and had a literate and educated aristocracy (admittedly, education was caste-based, but even so, a greater percentage of the world’s population read Mayan glyphs than any 8th-century Western European vernacular script).

- by the time the Muslims made the much-vaunted introduction of the idea of “zero” to European mathematicians, the Maya had been using their own, independently-arrived at “zero” for quite some time. And while the Arabic numeral system was easier to use for calculation than the Roman, it still requires various combinations of 9 different symbols to express numerals; the Mayan notation system used combinations of only 3 symbols (again admittedly, the use of face-glyphs as a concurrent numbering system makes this a somewhat-arguable statement).

- among the Maya, priests exercised power of which contemporaneous Popes could only have dreamed. A complex pantheon of no fewer than 166 gods – most with multiple aspects – exercised influence over this world, the 13 levels of heaven, and the 9 layers of hell. Political decision-making was astrology- and omen-based, and the performance of complex rituals and calendrical observance were seen as integral to the proper functioning of the entirety of creation.

- Maya architecture, with all its regional uniqueness and astronomical floorplanning, remains, of course, uniformly astounding:

Things They Were, Things They Weren’t

The Maya did perform human sacrifice, though the scale was relatively limited when compared to some of the later Mesoamerican societies. More common was the practice of sacrificial bloodletting, some of which involved some pretty intense tests of faith:

For the Maya, blood sacrifice was necessary for the survival of both gods and people, sending human energy skyward and receiving divine power in return. A king used an obsidian knife or a stingray spine to cut his penis, allowing the blood to fall onto paper held in a bowl. Kings’ wives also took part in this ritual by pulling a rope with thorns attached through their tongues. The blood-stained paper was burned, the rising smoke directly communicating with the Sky World.

From the website of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, which hosted a significant Mayan exhibition in the late 1990s

Maya religion – like that of the later Aztecs – was based upon the idea of sacrifice. Just as the Aztec creation story tells of a poor, weak god who sacrifices himself to become the Sun, so, too, does the 18th-century translation of the Mayan creation story Popol Vuh set an example of selfless giving on the part of individuals so that the whole of creation might be maintained. This made their faith a bit dour: most Maya were resigned to spending their afterlife in a cold, dank underworld. There’s also an argument to be made that says their vast ceremonial centers were constructed as much on the basis of avoiding divine retribution as they were honoring the gods.

Deciphering the Maya writing system proved to be the key to understanding all this. It’s a fascinating story in its own right (complete with treasures spirited off to the USSR from a burning Berlin Public Library), and it’s not yet complete. Mayan writing, based as it is on regional dialects, artistic choice, and changing cultural trends, is still difficult to interpret. It uses a combination of phonetic symbols and ideograms, though sometimes the two are used interchangeably. Additionally, the construction of particular glyph “blocks” is left largely up to the sculptor/scribe, so those of different city-states might record the same word in a number of different ways.

Optional Excursion from the Cave of the Moonbat: If you’re up for it, you can try to figure out how to spell your name in phonetic glyphs here. Be sure’n pay attention to the principal of Synharmony, and ladies, don’t forget to precede the syllables of your name with a “Na” glyph.

The Mayan calendar figures prominently in the story of the Star Wars, and is, in its own right, one of the greatest achievements in all of Ancient and Classical history. It was extremely intricate, consisting of two intermeshed “gears,” a ritual one of 260 days, and a solar one of 365 days, which regulated the timing of religious or agricultural events and activities. It really is a fascinating subject – comes complete with an unlucky week at the end of every year and a fast-approaching doomsday – but it’s just too much to delve into in a diary where I’ve written 4 pages and haven’t yet gotten to the main story. (fwiw, I did wind up historioranting on the calendar and the Maya doomsday prophesy back in March, 2008 – and it turned into my second highest comment-getter ever: Apocalypse 2012! – u.m.)

Finally, the Maya were a lot of things, but they were never a unified empire. ;No Ceasar ever rose from among the elites to unite the city-states under one banner – indeed, politically, the Mayan realm was much more like Ancient Greece than Ancient Rome. Cities rose and fell in prominence and power as alliances shifted, battles were won and lost, and powerful families disintegrated as brothers stabbed one another in the back. As more and more carved monoliths and ceremonial staircases have been unearthed by archaeologists, it’s become apparent that the nobility among the various Maya cities were every bit as intertwined as that of the Greeks and the proto-aristocratic houses of Europe.

It was an especially violent confluence of all these things – religion and politics, power and control, and human frailties writ large – that led to the Star Wars. Well, that and competition between two regional superpowers over trade routes.

Would you be surprised if I told you it all came down to money?

Tikal was one of these mighty cities. Today, its ruins are some of the better-restored, and certainly the most photographed, in all of Guatemala – you may even recognize the ornamental roof combs from another story of Star Wars, as stock footage of treetop-level Tikal was used for exterior shots of the rebel base in George Lucas’ Star Wars: A New Hope. This is likely a coincidence; the story of the Tikal-centered Star War we’re discussing tonight was not known until excavations at sites some distance removed from Tikal (and 20+ years later) revealed carvings that allowed Mayanists to piece together the tale.

Tikal was one of these mighty cities. Today, its ruins are some of the better-restored, and certainly the most photographed, in all of Guatemala – you may even recognize the ornamental roof combs from another story of Star Wars, as stock footage of treetop-level Tikal was used for exterior shots of the rebel base in George Lucas’ Star Wars: A New Hope. This is likely a coincidence; the story of the Tikal-centered Star War we’re discussing tonight was not known until excavations at sites some distance removed from Tikal (and 20+ years later) revealed carvings that allowed Mayanists to piece together the tale.

Historiorant: …and besides, as a devoted follower of all things Roddenberry – thus having long suffered the indignities of Palinesque argumentation at the hands of legions of Lucas aficionados – I’m not quite as willing as the Stars Wars types to anoint the man with the Joseph Campbell Award for Jungian Prescience.

Tikal’s traditional rival was Calakmul, located about 60 miles north of Tikal (again, think Ancient Greece) and situated in what is now the extreme south of the Mexican State of Chiapas. Though far less excavation work has been done at Calakmul, in the 6th century CE, the city rivaled Tikal in terms of prestige and power. The two vied for control of a corridor of trade routes that led from the Caribbean coast to the cities and interconnected routes branching off the Rio Usumacinta, currently part of the western border between Guatemala and Mexico (and how’s this for cool?: the name means “River of the Sacred Monkey”). The jungles and mountains to the north and south of this economically strategic corridor were nigh on impassable, even to the Maya (who were, btw, unencumbered by need to build their roads for wheeled carts – though they knew full well the properties of rolling things, vehicles with axles were never put into wide use. As Jared Diamond indicates, No Draft Animals = No Wheels).

Calakmul probably wasn’t the great city’s real name; it’s the invention (in Mayan, at least) of a 20th-century archaeologist. Like all Maya cities, it was laid out according to precise astronomical observations and mathematical computations, but was also a city built for defense, as can be seen in a 1932 photo of the northwestern defensive wall. It topped 6 meters (20 feet) in places.

Calakmul probably wasn’t the great city’s real name; it’s the invention (in Mayan, at least) of a 20th-century archaeologist. Like all Maya cities, it was laid out according to precise astronomical observations and mathematical computations, but was also a city built for defense, as can be seen in a 1932 photo of the northwestern defensive wall. It topped 6 meters (20 feet) in places.

It probably won’t surprise you to learn that there was a lot of political and military jockeying for the control of the various smaller cities that dotted the contested land. Colonies, vassal states, and military outposts like Caracol, Uaxactun, and Dos Pilas alternately dominated and fell under the control of the great powers, and above a certain level in the hierarchy of all the belligerents, many of the elite seem to have been related.

It probably won’t surprise you to learn that there was a lot of political and military jockeying for the control of the various smaller cities that dotted the contested land. Colonies, vassal states, and military outposts like Caracol, Uaxactun, and Dos Pilas alternately dominated and fell under the control of the great powers, and above a certain level in the hierarchy of all the belligerents, many of the elite seem to have been related.

The Feuding Children of Jaguar Claw I

Rising to power sometime around 350 CE, Toh-Chak-Ich’ak, the king who would come to be known as Great Jaguar Claw, effectively founded the state that became Tikal. It was he who led the fledgling empire to victory against Uaxactun, he who – along with a guy aptly named Spearthrower Owl – introduced the atlatl to the highland Maya, he who constructed the most sacred sanctuary in the heart of the Great Acropolis of Tikal.

He and his immediate descendents were great admirers of Teotihuacan, the mighty metropolis whose Pyramids of the Sun and Moon are often associated with the Aztecs, but who in fact pre-date the Mexica arrival in the Valley of Mexico by more than 1000 years.

Historiorant: The outskirts of Teotihuacan, an archaeological treasure and UN World Heritage Site, are currently being defiled by the presence of an accursed Wal-Mart.

Jaguar Claw I established a dynasty that was to last three generations, with each one marked by increasing tension, warfare, and cultural disintegration – and less and less influence from Teotihuacan. Indeed, by the time Tikal picked a fight it couldn’t win (in the mid-500s CE), cultural input from Valley of Mexico had slowed to a trickle.

The family of Jaguar Claw I had spread its influence far and wide; there may even have been a lineage relationship between the patrons of Tikal (Jaguar Claw) and Calakmul (Fire Jaguar Claw). By the 6th century CE, however, any peace this might have bought had gone right out the window. Tikal was heavy-handed in the way it dealt with friend and foe alike, and saw more than a few of its thought-to-be-sealed-in-blood alliances fall apart as younger siblings and lesser lords switched over to Calakmul in exchange for a share of the spoils of Tikal.

Medieval Politics, Jungle-Style

Tikal was hugely distressed in 546 CE, when it learned that Calakmul had installed a ruler of its choosing at Naranjo, only 25 miles (42 km) from Tikal. Angered at the defection but unwilling to risk open confrontation with Calakmul, Double Bird, from his seat at the Great Acropolis, seems to have tried to play some power politics by instigating a rebellion against Calakmul and installing a leader more amenable to Tikal at Caracol, about 45 miles (75 km) distant, in 553 CE. Whatever Double Bird thought was going to happen, it didn’t: Tikal found itself at war with Caracol only three years after inaugurating its king.

Ritual, ceremony, and meticulous attention to detail were part of the Maya way of war. In 556, for example, Tikal had had enough of Caracol’s crap, and announced its intention to wage an Axe War against its erstwhile ally. In an Axe War, the objective is to vandalize and destroy (as opposed to, say, a Flower War, in which the objective was the capture of prisoners), and the announcement of this one took Caracol by surprise. The city was badly damaged by the attack, as indicated by Stela 17 at Tikal, which mentions something about a “chopping” or “cutting” incident at “Flint Mountain,” – a glyph now identified as Caracol.

The Star War and the Hiatus

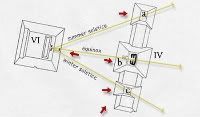

Caracol licked its wounds and cut some deals with Calakmul, and in 562 CE, came roaring back with an horrific vengeance. In that year, an alliance against Tikal gathered and launched a Star War. This particular type of war were designed by the very precision of their timing to unleash the greatest evil possible upon an enemy – they always corresponded with the first heliacal rising of Venus in the morning sky, a portent of great malevolence in Maya cosmology.

It’s from a carving on an altar at Caracol that we learn of the defeat of Tikal, and from a stela at Naranjo that Caracol and Naranjo were now allies on the same, Calakmul-supporting side. Tikal found itself ringed by enemies, and quite possibly placed under the harshest sort of puppet rule imaginable. The Star War of Caracol marks the beginning of a period known as the Hiatus; Mayarealm describes the archaeological silence precipitated in the aftermath of the struggle:

With this definitive defeat, Tikal fell silent. There are no known carved monuments, no inscriptions of any kind recorded at the city for a period of 125 years. Nor were any structures dedicated or lintels installed for the glory of a ruler. Because the silence falls precisely during the transition between cultural periods, the problem of analysis of events is especially difficult. The Hiatus itself is unique to the city of Tikal. (emphasis mine – u.m.)

Carvings from nearby cities indicate that everything was cool from 593 to 672 CE, with trade going on as normal everywhere except Tikal. It appears they were allowed to keep their own rulers (presumably on a pretty short, Calakmul-held leash), but in Tikal, the break with the city’s storied past seems to have been deliberate and systematic: there began a period of monument destruction (a la the Egyptians after Akhenaton) around this same time.

What Goes Around, Comes Around

In the early 7th century, Tikal was surrounded by enemies – Calakmul to the north, Naranjo in the east, Caracol to the southeast, and even a traitorous ruler of the Jaguar Claw line defecting in the recently-established fortress of Dos Pilas in the west. Tikal’s ancient allies were too distant – Palenque (Mexico) in the north and Copan (Honduras) in the south – to render assistance, and so the city bore its century-long misery in effective quarantine.

Dos Pilas, strategically located 70 miles (113 km) to the southwest, is a great example of why things seemed so bleak for the Lords of Tikal. There a leader of the Jaguar Claw line was able to establish his four year-old brother as ruler in 629 CE. The young king, Balaj Chan K’awiil, remained loyal to Tikal to the point of rebellion – at least until he was defeated by Calakmul. He was made to swear allegiance to his new overlords – and rather graphically at that:

Under the banner of Calakmul, K’awiil waged war against Tikal for a decade and eventually sacked the city-state, carrying its ruler–his brother–and other members of the nobility back to Dos Pilas to be killed.

The text at Dos Pilas describes the bloodshed and the celebration that followed. “The west section of the steps was very graphic,” said Fahsen. “It says, ‘Blood was pooled and the skulls of the people of the central place of Tikal were piled up.’ The final glyphs describe the king of Dos Pilas doing a victory dance.”

K’awiil subsequently renamed Dos Pilas “New Tikal” by usurping Old Tikal’s founding glyph and using it as his own, probably with Calakmul’s support. Tikal was able to do very little about this (in a military/vengeance sense), and Calakmul was only too happy to recognize the newbie as the legitimate government of all things Tikal.

The insult was not forgotten, however: In 672 CE, as Islam was spreading across North Africa and Southwest Asia and the Tang Dynasty was energetically absorbing Korea, Tikal launched a Star War of its own, with its target the renegade state of Dos Pilas. Then under the control of Shield Skull, Dos Pilas found itself at the mercy of a resurgent Tikal (guess their guard had slipped a little), which subsequently set about avenging more than a century’s worth of humiliating subjugation. Eventually, Tikal would conquer Calakmul itself, only to find itself so weakened by the effort that a whole new round of intercity warfare began.

One can pretty clearly piece together what happened: the maintaining of an occupation in hostile territory for more than 100 years became both expensive and tiresome for Dos Pilas, and control over the affairs of Tikal – once so tight-leashed – began to slip. The city rebuilt itself while the allies against it quarreled over who was going to take care of the “Tikal problem,” and by the time they finally coordinated a response, thousands of really angry atlatl-throwers were approaching their walls.

Historiorant: And the Gears of Time Grind On…

The cycle of warfare continued, almost unabated, until 900 CE or thereabouts, when the Classic Maya civilization rather abruptly drops from the historical radar screen. Oh, sure, there was a 300-or-so-year Post Classic period – but it was marked largely by decline in the southern Maya realm and by creeping Toltec dominance in the north. The age of great kings, powerful armies, and the glory and deprivation of empire had passed; by the time the Spanish arrived, the Maya had readjusted to a village-based economy, leaving the brilliant cities of their ancestors to the ministrations of the rainforest.

The cycle of warfare continued, almost unabated, until 900 CE or thereabouts, when the Classic Maya civilization rather abruptly drops from the historical radar screen. Oh, sure, there was a 300-or-so-year Post Classic period – but it was marked largely by decline in the southern Maya realm and by creeping Toltec dominance in the north. The age of great kings, powerful armies, and the glory and deprivation of empire had passed; by the time the Spanish arrived, the Maya had readjusted to a village-based economy, leaving the brilliant cities of their ancestors to the ministrations of the rainforest.

That’s not to say that the events depicted in Apocalypto are all that far-fetched – there could well have been a return to the old ways (and the old cities) as strange ships began appearing on their coasts – but I kinda think Mel’s choice of subject for the film was predicated by two things, both unrelated to historical accuracy. The first is that he definitely wanted to show a ritual Mesoamerican human sacrifice; the other is that doing a movie (or at least, doing one right) about Cortez, Moctecuzoma, and the Battle of Tenochtitlan would be obscenely expensive.

The stories of the fall of the Classic Maya and of the centuries-later Spanish colonization of the Mayan lands – complete with one of the worst-ever crimes against History itself – are the stuff of another diary. Tonight, I think we should look at the Mayan concept of cyclical time, how everything is as predictable as it is inevitable – if only one knows what to look for. I’ve no idea what a Mayan calendar-keeper would say about the upcoming election, but I can predict that he’d advise us that the answer is right in front of us, hidden in plain sight amidst the vast landscape of our own history.

In Cave News, look for a special Tuesday-night edition of History for Kossacks this week. Georgia’s been on my mind of late, as has Jim Martin‘s bid for the Senate seat currently being defiled by Saxby Chambliss, so fix yourself a mint julep and by all means, stop by the Cave of the Moonbat and set a spell. Oh, and take out your wallet first – it makes the settin’ more comfortable.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

16 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

makes me wonder about something odd, something that might make for a good diary someday: If you had a time machine and could alter up to three events in world history, what would they be?

You are not allowed to tell me how much I suck as an historian in my new series in Cafe Discovery.

=8-0

my kitty maya tried to paw my monitor when i reached the tapestry pic! she does have great taste. 🙂

A contrast with all of this warfare is the 19th Century War of the Castes in the Yucatan, between the Maya and the central Mexican Government. Long story short, the Mayan forces had the Mexican forces surrounded in the colonial city of Merida, which is on the ocean. As the siege wore on, it became time to plant corn, so the Mayan forces withdrew to plant, breaking the siege. The war continued another 60+ year, until 1911, when in a scene reminiscent of Hanoi in 1975, the Mexican central government quit and withdrew. It wasn’t until 1935 that Mayans in Quintana Roo, specifically in Tulum, decided to recognize the Mexican government and end the war.

As punishment for the siege of Merida, the Yucatan peninsula was broken up into 3 states: Yucatan (in the north), Quintana Roo in the east where Cancun is now, and Campeche in the west.

Tulum, which has an amazing ruin overlooking the Caribbean, 73 years since its recognition of Mexico City, is still fundamentally a Mayan city.

Mayan descendants…they would have loved this! And the site for the glyph names!

Thanks so much.

So cool. Better late than never!