(7:30PM EST – promoted by Nightprowlkitty)

This Sunday’s New York Times Magazine contains a feature titled Is Obama the End of Black Politics? Its an attempt by Matt Bai to explain the shifting ground on which both the issues and the politics of the African American community stand today. This is an issue that has been bubbling beneath the surface (and sometimes above) since Obama won the Iowa caucuses.

Within hours of Obama’s victory in Iowa, however, Clinton’s black support began to crumble. Black voters, young and old, simply hadn’t believed that a black man could win in white states; when he did, a wave of pride swept through African-American neighborhoods in the South.

That wave caught many long-time civil rights leaders and Black politicians by surprise…a shift had happened and they were caught unawares.

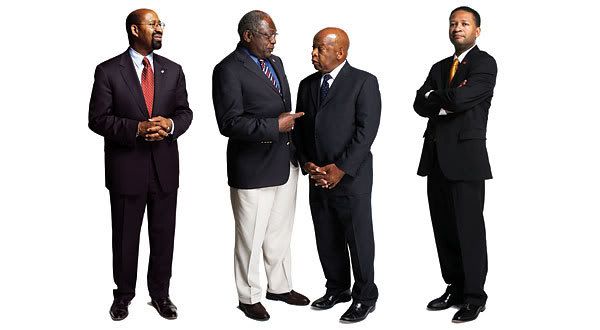

From left to right are Mayor Michael Nutter of Philadelphia; Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina; Representative John Lewis of Georgia; and Representative Artur Davis of Alabama.

You can see that shift in the stories of a couple of people Bai interviewed for this article…first of all, Elijah Cummings:

For black Americans born in the 20th century, the chasms of experience that separate one generation from the next- those who came of age before the movement, those who lived it, those who came along after – have always been hard to traverse. Elijah Cummings, the former chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus and an early Obama supporter, told me a story about watching his father, a South Carolina sharecropper with a fourth-grade education, weep uncontrollably when Cummings was sworn in as a representative in 1996. Afterward, Cummings asked his dad if he had been crying tears of joy. “Oh, you know, I’m happy,” his father replied. “But now I realize, had I been given the opportunity, what I could have been. And I’m about to die.” In any community shadowed by oppression, pride and bitterness can be hard to untangle.

and then Cory Booker:

When I met last month with Cory Booker, the mayor of Newark who at 39 is already something of a national sensation, he told me that he had just finished reading, belatedly, Obama’s memoir “Dreams From My Father.” He said passages about Obama’s youth in Hawaii had reminded him of his own experience with subtle racism in the affluent, mostly white suburb of Harrington Park, N.J. “You know, what it’s like growing up every single day and having people ask to touch your hair because they’ve never seen hair like that,” Booker said. “To have the entire class laugh and giggle when somebody pronounces ‘Niger’ as ‘nigger.’ The constant bombardment of that kind of thing really affects your spirit, and it’s every single day. Like when people want to come back from a vacation and compare their tan to yours and joke about being black.”

No doubt these were searing experiences for Booker, and I had to wince as he ticked them off, recognizing too much of myself and my white classmates from the 1980s in the imagery. But as Booker himself noted, they are a world away from the reality that was pounded into civil rights activists like his parents, to whom racism meant dogs and hoses and segregated schools and luncheonettes. You can imagine what James Clyburn – still haunted by the vivid memory of the moment he found out that his erudite father had never been allowed to graduate from high school – would make of the lifelong trauma caused by suburban kids asking to feel your hair.

Bai explains the transition this way:

Black leaders who rose to political power in the years after the civil rights marches came almost entirely from the pulpit and the movement, and they have always defined leadership, in broad terms, as speaking for black Americans. They saw their job, principally, as confronting an inherently racist white establishment, which in terms of sheer career advancement was their only real option anyway. For almost every one of the talented black politicians who came of age in the postwar years, like James Clyburn and Charles Rangel, the pinnacle of power, if you did everything right, lay in one of two offices: City Hall or the House of Representatives. That was as far as you could travel in politics with a mostly black constituency. Until the 1990s, even black politicians with wide support among white voters failed in their attempts to win statewide, with only one exception (Edward Brooke, who was elected to the U.S. Senate from Massachusetts in 1966)…

This newly emerging class of black politicians, however, men (and a few women) closer in age to Obama and Jesse Jr., seek a broader political brief. Comfortable inside the establishment, bred at universities rather than seminaries, they are just as likely to see themselves as ambassadors to the black community as they are to see themselves as spokesmen for it…Their ambitions range well beyond safely black seats.

Some of the other emerging leaders Bai talked to for this article include Alabama Representative Artur Davis, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, NAACP President Benjamin Jealous, Jack and Jill Politics blogger Cheryl Contee (also known as Jill Tubman), and Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick.

At one point, Bai talks about Van Jones, who is one of the people behind Color of Change and Green for All. If you want to hear what people from this new generation of African American leadership sound like, here’s Van Jones in a guest appearance on The Colbert Report.

7 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

that “Somethings Gotta Give.”

Matt Bai is an idiot.

Connecticut is a small state.