For anyone born before 1970 or so, there are certain images that are come to mind whenever the name “Iran” is uttered: stern, bearded men in black robes, angry crowds, graphics depicting blindfolded American citizens with things like “Day 334” stamped over them, Ollie North bravely disgracing his uniform and perjuring himself, John McSame exploring the intersection of 1960s pop music and the idea of raining death from the skies. In short, the past 30 years haven’t exactly been a model of how nations ought to think of one another.

Join me, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where tonight we’ll take a last look – a Parthian shot, if you will – at the recent history of Iran. Maybe, just maybe, we’ll get past some of the more extreme caricatures the Traditional Media has been foisting upon us – and perhaps be able to start formulating a de-Bushified foreign policy that relies less on blustering incompetence and more on genuine historical understanding.

Life wasn’t easy for fundamentalist Shi’a Iranians in 1902, the year of Ruhollah Musawi Khomeini’s birth. The Qajar dynasty was on its last legs, secularists were everywhere, and when the Pahlavis seized the reins of power in the 1920’s, things got even worse for the old-school Shiite power structure.

Portrait of an Ayatollah as a Young Man

Ruhollah Musawi was born on September 24, 1902 (a birthday shared by Muhammad’s wife Fatima), in the town of Khomein, about 120 km southwest of Qom. He spent much of his life feeling powerless and oppressed, and not without some justification. His father, a prominent Shi’a cleric, was killed before he turned a year old, and he lost both his mother and the aunt who had raised him when he was sixteen. So it was that when he took up the cloth – his family background included many Islamic scholars, not to mention descent from Musa al-Kazim, the 7th Imam, so this wouldn’t have come as much of a surprise – he gravitated toward scholars whose views sought to explain the suffering of his early life. According to Ted Thornton’s History of the Middle East Database:

Ruhollah Musawi was born on September 24, 1902 (a birthday shared by Muhammad’s wife Fatima), in the town of Khomein, about 120 km southwest of Qom. He spent much of his life feeling powerless and oppressed, and not without some justification. His father, a prominent Shi’a cleric, was killed before he turned a year old, and he lost both his mother and the aunt who had raised him when he was sixteen. So it was that when he took up the cloth – his family background included many Islamic scholars, not to mention descent from Musa al-Kazim, the 7th Imam, so this wouldn’t have come as much of a surprise – he gravitated toward scholars whose views sought to explain the suffering of his early life. According to Ted Thornton’s History of the Middle East Database:

Ruhollah’s education reflected a strong Persian dualist outlook on the world: a tendency to draw sharp boundaries between the worlds of light and darkness, between black and white, between haq (“truth”) and batel (“falsehood”). This approach to the world, under girded by a traditional Iranian Shia conviction that the world is unsafe for Shiites, that neither the Prophet Muhammad, his family, nor any of the twelve Shia imams died a natural death (“We are either poisoned or killed.”), contributed to the construction within Khomeini of the uncompromising personality of one who feels relentlessly persecuted.

Khomeini took up teaching at the Dar al-Shafa school in Qom, lecturing and writing for most of the middle part of the 20th century in the areas of jurisprudence (i.e. Shari’a law), philosophy, and mysticism ( `Irfan, sometimes translated as “Islamic gnosis”). He was profoundly impressed by the writings of Rumi and Ibn ‘Arabi, both of whom espoused the idea of a “Perfect Man,” one destined to lead society into a golden age of religion-inspired unity. Perhaps not surprisingly, by the end of his life, Khomeini was reasonably certain that he was that guy.

Khomeini maintained his vision of an Islamic state as his colleagues endured ever more depredations under the shah. Eventually he found himself out in front of the reformers, and by the time he turned 60, his voiced carried great weight. It was with the shah’s announcement of the White Revolution in 1963 that Khomeini entered national politics in a big way, publicly denouncing the program as entirely too Westernizing. He was jailed for his opposition, but was gratified to learn that his arrest had sparked demonstrations in all of Iran’s religious centers. Released in 1964, he quickly denounced the United States, too, for which he was exiled by a shah who, as we saw last week (in what I must say was a rather ill-attended historiorant – tsk, tsk), pretty much owed his spot on the Peacock Throne to the Central Intelligence Agency. After a brief stint in Turkey, Khomeini set up shop in Najaf, Iraq, burial place of Ali, the 4th – and first Shi’a – Imam. From Najaf, he would snipe at the shah’s government until 1978.

In that year, as the government of the shah was being increasingly destabilized by rioting – much of which was being orchestrated from Najaf – the Ayatollah pissed off the easy-to-piss-off Vice President of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, and was expelled by Iraqis in collusion with the Iranian government. He wound up on the sofa circuit, finally landing at a supporter’s place in a suburb of Paris. From there, Khomeini embarked on a very public organization and radicalization of his supporters back home, playing the world media in a way it had never been played before. A Western world unfamiliar with even the most basic tenants of Islam (check out pre-Carter era high school textbooks, or any recent statement by Grampa McCain, if you don’t believe me) didn’t really understand what was going on, and tried to put the turmoil unfolding in the autumn of 1978 in terms it could understand. A glossary of the times put together with input from Joe Sixpack might’ve looked something like this:

In that year, as the government of the shah was being increasingly destabilized by rioting – much of which was being orchestrated from Najaf – the Ayatollah pissed off the easy-to-piss-off Vice President of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, and was expelled by Iraqis in collusion with the Iranian government. He wound up on the sofa circuit, finally landing at a supporter’s place in a suburb of Paris. From there, Khomeini embarked on a very public organization and radicalization of his supporters back home, playing the world media in a way it had never been played before. A Western world unfamiliar with even the most basic tenants of Islam (check out pre-Carter era high school textbooks, or any recent statement by Grampa McCain, if you don’t believe me) didn’t really understand what was going on, and tried to put the turmoil unfolding in the autumn of 1978 in terms it could understand. A glossary of the times put together with input from Joe Sixpack might’ve looked something like this:

- Iran – “One of them oil countries in the desert. Didn’t know it used to be called Persia. Ain’t never heard of no Cyrus the Great – he like a Roman or something?”

- Iranians – “Seem different from the Saudis somehow. At least they dress like normal American folks. They demonstrate a lot; they’re like the South Koreans of the Mideast.”

- Shah – “A king, one of those dictator guys with snazzy uniforms, lots of medals, and a totally hot wife who just so happens to share the unusual name Farah with the current hottest pinup in the United States – hey, you seen that poster of her in the bathing suit? I got it right next to the one of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders.”

- Iranian government – “This shah guy probably runs things with an iron fist – those guys always do – so it’s no wonder his people are pissed at him. If they want a religious nut running their government, that’s their business.”

- Khomeini – “Weird religious guy who looks kind of ominous but sorta sounds like he’s fighting for what at least some people in Iran want. Don’t really know what a theocracy is.”

- Ayatollah – “Doesn’t that mean like ‘Muslim Pope’ or something?”

- Sunni, Shi’a, Ali, et al. – “I dunno, and this whole line of questioning is starting to cramp my style. Wanna just do some blow and head out to the disco?”

Khomeini, by contrast, knew exactly what he wanted, and expressed it quite clearly in 1979:

Your opponents, oppressed people, have never suffered. In the time of the taghut (idolatry; impurity), they never suffered because either they were in agreement with the regime and loyal to it, or they kept silent. Now you have spread the banquet of freedom in front of them and they have sat down to eat. Xenomaniacs, people infatuated with the West, empty people, people with no content! Come to your senses; do not try to westernize everything you have! Look at the West, and see who the people are in the West that present themselves as champions of human rights and what their aims are. Is it human rights they really care about, or the rights of the superpowers? What they really want to secure are the rights of the superpowers. Our jurists should not follow or imitate them. You should implement human rights as the working classes of our society understand them. Yes, they are the real Society for the Defense of Human Rights. They are the ones who secure the well-being of humanity; they work while you talk; for they are Muslims and Islam cares about humanity. You who have chosen a course other than Islam–you do nothing for humanity. All you do is write and speak in an effort to divert our movement from its course.

But as for those who want to divert our movement from its course, who have in mind treachery against Islam and the nation, who consider Islam incapable of running the affairs of our country despite its record of 1400 years—they have nothing at all to do with our people, and this must be made clear. How much you talk about the West, claiming that we must measure Islam in accordance with Western criteria! What an error! It was the mosques that created this Revolution, the mosques that brought this movement into being. The mihrab was a place not only for preaching, but also for war–war against both the devil within and the tyrannical powers without. So preserve your mosques, O people. Intellectuals, do not be Western-style intellectuals, imported intellectuals; do your share to preserve the mosques!

Glossary-Based Sidenote: The word “Ayatollah” (“Sign of God”) is an honorific title bestowed upon Shi’a clerics by religious leaders and students; usually it is attested to by teachers after significant effort in the fields of jurisprudence, ethics, and/or philosophy. One interesting feature of being deemed an “Ayatollah” is that the honoree takes on the name of their hometown or region; “Ayatollah Khomeini” would mean something akin to “The Sign of God from Khomein.” People started applying the term, and the geography-based surname, to Ruhollah Musawi around 1930.

Happy Days are Here Again

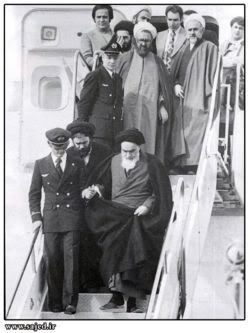

In the Majles, pressure to initiate reforms built throughout 1978, and culminated with the appointment of Shapour Bakhtiar to the office of prime minister on January 3rd, 1979, to replace a general who supported the shah. On January 16, the shah announced he would be taking a short trip overseas. He would never set his royal butt on the Peacock Throne – nor royal foot in his homeland – again.

The Ayatollah would, though, and jubilant preparations were made for his return. On February 1st, he arrived in Teheran, and by March 30-31, had orchestrated a successful referendum on the establishment of an Islamic republic. If the election results are to be believed, 98% of Iranians favored exchanging monarchy for a theocratic state.

The Ayatollah would, though, and jubilant preparations were made for his return. On February 1st, he arrived in Teheran, and by March 30-31, had orchestrated a successful referendum on the establishment of an Islamic republic. If the election results are to be believed, 98% of Iranians favored exchanging monarchy for a theocratic state.

Khomeini and the boys were, of course, the big winners in that election and the subsequent plebiscites to ratify a new constitution and establish a means of electing a president (don’t worry: candidates were all screened by the newly-established Council of Guardians, which was made up of clerics – you don’t get their stamp of approval, you don’t get to run). After Mehdi Bazargan served as prime minister under the provisional government, Khomeini got Abulhassan Banisadr as his presidential – Iran’s first president ever, btw – point man in February, 1980. He also got himself named “Supreme Leader for Life” and was officially decreed the “Leader of the Revolution.”

The Ayatollah had a broad and unusually liberal sense of social utopianism, a trait he offset by governing through the harsh totalitarianism. Rather than be accused of leading the reader to a particular conclusion, I’ll list a few of his domestic policies in no particular order, and let the reader reach his/her own conclusions – or perhaps embarkation points for a research trip around the net:

- He promised (though never delivered) free gasoline and utilities

- He rounded up, tortured, and killed dissenters

- He enforced a strict Islamic dress code, including a return to chadors for women

- He shattered traditional conservative views regarding the role of women in society: so long as she were properly attired, an Iranian woman was free to work outside the home (employment among women skyrocketed in the early days of the Ayatollah’s reign). This was a marked change from the fashion-liberal/socially-paternalistic way of life of women under the shahs

- Shari’a law was imposed and the Quran became the founding document of the Iranian legal system

- He issued a fatwa proclaiming the right of those with hormonal imbalances to undergo gender reassignment surgery and therapy, and to change their birth certificates to reflect the new gender

- He supported programs leading to advanced degrees for women; however, he used his control of the state apparatus to channel educated women into fields like gynecology and pediatrics and away from things like civil engineering

- He supported organ transplants, family planning, and the distribution of contraceptives

- He issued a fatwa in 1989 calling for the death of Salman Rushdie for having written The Satanic Verses, a work of fiction which suggested that the Quran had not been properly preserved

- He burned books

Most other aspects of life changed, too, and many Iranians of means fled overseas as the Revolution’s grasp of the country became more complete. Despite close ties with the United States under the Shah, worldly, westernized Iranians now found that door slammed shut by an event yet to be recounted (don’t worry, we’re almost there), and in Europe, as often as not, found themselves mistaken for the die-hard Khomeini supporters who burned themselves into the public consciousness through the news every night.

How to Humiliate a Superpower

Demonstrations outside the US Embassy in Teheran were common throughout 1979, and got worse when President Carter allowed the deposed Shah – now suffering from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – into the United States for medical treatment. The young supporters of Khomeini suddenly remembered the U.S.-backed coup that had toppled champion-of-the-people Muhammad Mossadeq back in the 50’s to put this very Shah in power; to them, the evidence of collusion for another coup was clear. Eventually the Shah left the US, going first to Panama, then to Egypt, where he died on July 27th, 1980; he’s buried alongside Egypt’s last Mameluke king, Farouk, in Cairo. In Iran, Khomeini played to his base and used the Shah’s flight to point fingers at the enemies of Islam.

Demonstrations outside the US Embassy in Teheran were common throughout 1979, and got worse when President Carter allowed the deposed Shah – now suffering from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – into the United States for medical treatment. The young supporters of Khomeini suddenly remembered the U.S.-backed coup that had toppled champion-of-the-people Muhammad Mossadeq back in the 50’s to put this very Shah in power; to them, the evidence of collusion for another coup was clear. Eventually the Shah left the US, going first to Panama, then to Egypt, where he died on July 27th, 1980; he’s buried alongside Egypt’s last Mameluke king, Farouk, in Cairo. In Iran, Khomeini played to his base and used the Shah’s flight to point fingers at the enemies of Islam.

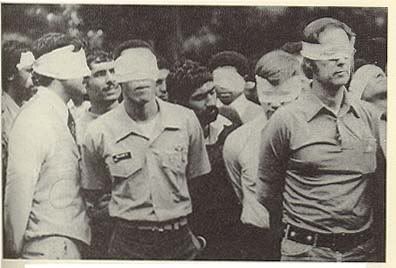

By November 1st, he was calling the United States the “Great Satan” and urging demonstrations against US and Israeli interests. In a move he later applauded (but maintained he didn’t plan or directly sanction) on November 4th, a mob estimated between 300 and 1200 hardcore supporters stormed the US Embassy and took 66 personnel hostage. Thirteen of these were released on November 19-20, 1979, and another one on July 11, 1980; 52 were held through out the entire ordeal.

It went on for 444 days. Nightly, images of bedraggled Americans – heads swaddled and faces obscured with broad strips of cloth, seemingly to showcase the inhumanity of the whole spectacle – were beamed into the living rooms of horrified, pissed-off, and thoroughly impotent citizens back home.

Historiorant/Note to Younger Kossacks Hard as it may be to believe, there was a time, not so long ago in the greater scheme of things, when the media regularly aired reports and documentaries critical of the government. This was seen by the people of that era as a necessary part of democracy, and the reporting was done by men and women with equal measures of balls and integrity. To the eternal shame of the modern crop of typists who daily piss on the noblest credos of their profession in pursuit of ratings, market share, and circulation, these ideas are now regarded as quaint.

Carter tried a military option, and it failed. I’ll not try to describe Operation EAGLE CLAW, nor adjudicate who or what is to blame for the failure – these are the things of another diary altogether – so I’ll just try’n give the bare bones of two versions of what happened at a landing strip in the Great Salt Desert near Tabas on the night of April 24-25, 1980:

1. The Carter administration rather tersely announced that a rescue had been attempted; a helicopter crashed into a C-130 transport plane, causing an explosion which killed eight and wounded several more; and that the mission was aborted. It should be noted that the online version of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library is not particularly helpful in researching the crisis or attempts to resolve it.

2. The Iranians were waiting for the Americans to arrive, and greeted them with a fusillade of gunfire when they landed. This would account for why five helicopters (some containing highly sensitive intel) were left behind.

3. Everything that could go wrong, did. In this version, which seems to this historioranter to be the most likely one, the plan itself (at least on paper) was sound and operational security did not lead to leaks, but Murphy’s Law asserted itself with a vengeance. According to this excellent article from Atlantic Online, the rescuers were obliged to play by ear – or seek presidential advice for how to deal with – situations ranging from unpredictable dust storms to civilian buses unexpectedly rumbling through the staging area.

No matter what caused the Desert One disaster, the failed rescue attempt had both long-term and short-term ramifications. In the long term, the flaws in special ops logistics and command and control revealed by the mission would eventually result in the creation of the Special Operations Command, now one of the key players in the deployments in Iraq (ironically – or prophetically? – on Iran’s western border) and Afghanistan (on the eastern border). In the short term, the images of burning American wreckage in the Iranian desert further demoralized the US, emboldened Iran, made our allies think twice about our competence, and aged Jimmy Carter an extra twelve years in the span of a couple of weeks. Though he did plan an even zanier second rescue mission (in which cargo planes fitted with retro-firing jet engines would land and take off inside a soccer stadium), it was never carried out.

Khomeini grew more anxious to settle the crisis as 1980 wore on. The Shah died on July 27, removing one bone of contention, and in September, Iraq, now being led by Saddam Hussein, launched an invasion. The Ayatollah knew he had already destroyed Carter’s chances of re-election, and so resisted entering into mediated discussions with Washington until after the US voted in early November. It is this climate which gave rise to the theories surrounding the ” October Surprise (beware, link-clickers: conspiracy theories ahead),” the idea that VP candidate/ex-CIA chief George Bush the Elder met with representatives of the Ayatollah’s government and made promises of military aid and the unfreezing of Iranian assets in US banks in exchange for a vow not to release the hostages until after the US election. If true, this would mean that the current wave of Republican treason has origins further back than many of us thought to look.

Maybe there was a deal, or maybe Khomeini just really, really hated Jimmy Carter, but the hostages were released on January 20, 1980, twenty minutes after Ronnie Ray-gun finished up his inaugural address. Does kinda make one go, “hmmmm.”

Sow the wind, reap the whirlwind

In the Algiers Accord of 1975, Iraq bribed Iran into cutting off support for Kurdish Iraqi rebels in exchange for 518 square kilometers of oil-soaked territory near Basra. By 1980, a more antagonistic leader had seized control in Iraq, and he wanted this land back.

Historiorant: Long-time Cave-dwellers know that even though I’m a ranting moonbat, I try to avoid using Hitler comparisons, which I find are usually hyperbolic and tend to degrade the nature of the discussion. There are times, however, when just such a comparison is apt, because occasionally what the Nazis did, and whatever it is that whoever I happen to be babbling about did, are pretty damn similar. Such was Saddam’s rationale for launching the Iran-Iraq War in September, 1980.

He played the Rhineland/Sudetenland/Polish Corridor gambit, only this time it was the beleaguered Arabs on the eastern banks of the Shatt al-Arab that needed rescuing from the alleged depredations of their traditional Persian Shi’a foe. Saddam spat upon the Algiers Agreement like Hitler on the Treaty of Versailles, all in the name of reuniting brothers marooned by the weak will of predecessor governments. For their part, the Iranians term the ensuing conflict “The Imposed War.”

He played the Rhineland/Sudetenland/Polish Corridor gambit, only this time it was the beleaguered Arabs on the eastern banks of the Shatt al-Arab that needed rescuing from the alleged depredations of their traditional Persian Shi’a foe. Saddam spat upon the Algiers Agreement like Hitler on the Treaty of Versailles, all in the name of reuniting brothers marooned by the weak will of predecessor governments. For their part, the Iranians term the ensuing conflict “The Imposed War.”

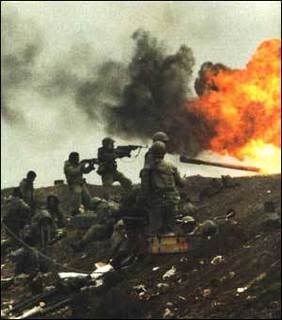

Saddam enjoyed some initial success, but his forces were stopped at Abadan, an Iranian city at the northern end of the Persian Gulf. At first disorganized and surprised, the Iranians recovered in good order, and by 1982, most of the fighting in what was turning into a war of attrition was occurring in Iraqi territory. There is a school of thought that says this was a tactical ploy by Saddam – he gets to choose the battlefields, digs in on his own ground, and is able to use the presence of the enemy on Iraqi soil as a recruiting tool.

The world chose sides, and the politics of the region made for some interesting bedfellows. The Soviet Union, China, France, and the United States (among others) provided support to both sides at different times in the war. Most (but not all) of the Arab world, as well as those European countries which experienced totalitarianism in the 20th century – West Germany, Spain, Yugoslavia, and Poland, among others – came out solidly for Iraq. Iran’s list of allies was something of a who’s who of military dictatorships and questionable democracies of the 80s: South Korea, Libya, Algeria, Taiwan, Vietnam, Argentina, South Africa, and Greece, and a handful of others.

The battlefields of the Iran/Iraq frontier must have seemed like the perfect playground for weapons testing to those men who passed for military intellects among the nascent neocon movement, then festering in the bowels of the Reagan White House. Iraq had bought most of its stuff from the Soviets, French (western arms merchant of last resort for many would-be deGaulles in the developing world), and Chinese. The Ayatollah had inherited much of his arsenal of aging US equipment from the Shah, but since he’d purged most of the generals as potential sources of coups, he was stuck with mullahs making military decisions based on reasoning that this part of the world hadn’t seen in hundreds of years – human wave attacks became the order of the day.

Thus, an Iraqi Air Force flying MiG-21 and Dassault F1 Mirage fighters and Tu-16 Badger bombers would face off against Iranian F-4s, F-5s, and Cobra attack helicopters. On the ground, both sides were weak in the self-propelled artillery department, which meant that infantry offensives could not be sustained. Iraq had the more professional force, but Iran had numbers; stalemate was pretty much inevitable.

The situation was similar at sea, where Iranians fired Chinese Silkworm missiles at tankers headed into or out of Iraqi ports, and Iraqis shot French Exocets at tankers which dealt with Iran. This “Tanker War”- and the mines it spawned – would eventually draw the US Navy into its largest surface engagement since the Second World War (Operation Praying Mantis, April 18, 1988), and would include such charming vignettes as a stray Iraqi fighter killing 37 Americans aboard the USS Stark (May 17, 1987) and the USS Vincennes shooting down an Iranian passenger jet with 290 aboard on July 3, 1988 (Happy Pickett’s Charge Day!).

Historiorant: Typical of military encounters between the US and Iran over the last 30 years, debate still rages as to whether this last was a catastrophic human error resulting in the deaths of hundreds of innocent noncombatants, or a set-up designed to make the US look bad. Here’s conspiracy-tinged site that might serve as a good jumping-off point to the wilder theories surrounding the Vincennes.

Rummy, Ollie, and the rest of the Cronies get their hands dirty

As the Great Buffoonicator’s special envoy to the Middle East from November, 1983, to May, 1984, Donald Rumsfeld had occasion to meet Saddam and have a little chat, man to like-minded man. They hammered out a deal in which the United States would hook Saddam up with “dual-use” (civilian and military) technologies – armored ambulances, mainframe computers, and the precursors to chemical weapons – in exchange for the US not providing Saddam with overt military aid (and providing the US with oil, of course – always the oil).

In the twisted, ratshit wasteland that is the neocon mind, selling the ability to make chemical weapons to Saddam Hussein was a way of getting Iran to do favors for the United States. By prolonging the war and providing the means for Saddam to gas over 100,000 Iranians (which, incidentally, puts Iran second only to Japan in terms of most citizens lost to weapons of mass destruction), Rummy was not only helping to kill off the hated hostage-takers, but getting them to use up and wear out their American equipment at the same time. So it was that when Ollie North betrayed this great nation and sold military hardware to the Iranians as part of the Iran/Contra series of lies, he wasn’t obligated to sell them the top-shelf stuff. The Iranians in 1984 needed spare parts to keep their Vietnam-era F4s flying, and that – in addition to 1000 pretty advanced TOW (Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided) anti-tank missiles – is what Ollie and Ronnie gave them.

In the twisted, ratshit wasteland that is the neocon mind, selling the ability to make chemical weapons to Saddam Hussein was a way of getting Iran to do favors for the United States. By prolonging the war and providing the means for Saddam to gas over 100,000 Iranians (which, incidentally, puts Iran second only to Japan in terms of most citizens lost to weapons of mass destruction), Rummy was not only helping to kill off the hated hostage-takers, but getting them to use up and wear out their American equipment at the same time. So it was that when Ollie North betrayed this great nation and sold military hardware to the Iranians as part of the Iran/Contra series of lies, he wasn’t obligated to sell them the top-shelf stuff. The Iranians in 1984 needed spare parts to keep their Vietnam-era F4s flying, and that – in addition to 1000 pretty advanced TOW (Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided) anti-tank missiles – is what Ollie and Ronnie gave them.

In exchange for dealing with the Americans – at first via the Israelis (the Ayatollah did have the capacity to recall the existence of Israel when it suited his purposes), then solo later on – Iran promised to get Hezbollah in Lebanon to release American hostages. They never did deliver on their end of the bargain. You might be asking “Where was our military to save these Americans?” I’d have to answer that they were gone, because Reagan – the Liberator of Grenada – cut and ran after he got 241 Marines, soldiers, and sailors killed in a scatterbrained deployment in Lebanon in October, 1983.

In exchange for dealing with the Americans – at first via the Israelis (the Ayatollah did have the capacity to recall the existence of Israel when it suited his purposes), then solo later on – Iran promised to get Hezbollah in Lebanon to release American hostages. They never did deliver on their end of the bargain. You might be asking “Where was our military to save these Americans?” I’d have to answer that they were gone, because Reagan – the Liberator of Grenada – cut and ran after he got 241 Marines, soldiers, and sailors killed in a scatterbrained deployment in Lebanon in October, 1983.

The Ayatollah played Reagan and his lackeys just as he’d played Carter, but there was still the war to contend with, and this had gotten truly nasty with Saddam’s introduction of chemicals. They started bombing each others’ cities, the Iraqis hitting Teheran with their Soviet-built strategic bombers, the Iranians lobbing Scuds into Baghdad (Saddam didn’t get Scuds of his own until 1988). In October, 1986, the Iraqi Air Force heroically threw itself against the schools, passenger railcars, and landed civilian airliners of Iran, killing thousands in deliberate attacks against the softest of noncombatant targets. Beginning in January, 1986, the “War of the Cities” claimed the lives of thousands as the Iraqis flew 226 sorties over a period of 42 days.

Iraq had sued for peace in 1982, but Khomeini, feeling that righteousness was on his side, demanded compensation for Iraq having started the war; his obstinacy in this regard would contribute significantly to the war dragging on as long as it did. His and Iran’s indignation increased even more as most of the world turned a blind eye to Saddam’s overt use of weapons of mass destruction against both Iran and the Kurds within his own country. Iran may have lost as many as 100,000 soldiers to chemical attack; to this day, thousands regularly seek medical attention and hundreds more remain permanently hospitalized. By the time the conflict ended in August, 1988, Iran had lost between 300,000 and 1,000,000 people to the war; Iraq had suffered a similarly uncertain but grotesquely high number of casualties.

Passing the Theocratic Torch

Ayatollah Khomeini died on June 3, 1989. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei pulled a move reminiscent of a Congressman-turned-lobbyist when he slid over from his role as President of the Republic to fill Khomeini’s considerable shoes as the nation’s religious leader. The Speaker of the Majles, Ali Akbar Rafsanjani – another cleric – was elevated to the presidency shortly thereafter. The new government had a slightly more secular approach to things than the Khomeini regime, and they quickly set about rebuilding Iran’s devastated infrastructure.

(Meanwhile, back in Iraq, Saddam was looking over his balance sheets. Kuwait had loaned him $14,000,000,000 for the war effort, and the quickest way of wiping the debt away seemed to lay in conquering his tiny, oil-rich, ill-defended neighbor…)

Even as it tried to recover from a devastating earthquake – almost 40,000 killed – in 1990, Iran endured fallout from events in surrounding countries throughout the remainder of the decade. While it joined in the international sanctions brought about by the First US-Iraq War, it allowed the fleeing Iraqi Air Force sanctuary (less than a decade after those same planes had performed strafing runs on Iranian elementary schools). Iran also provided sanctuary for up to a million Kurds fleeing northern Iraq in the aftermath of the war, and continued to play host to three times that many Afghanis, who had crossed the border to get away from the fighting with the Soviets. Rafsanjani was reelected in 1993, but ran into problems with Bill Clinton’s insistence that Iran not support terrorist groups and that it give up its nuclear weapons program. In 1995, the US suspended all trade with Iran, which may or may not have led to the election in 1997 of the more moderate Muhammad Khatami.

Regardless, the Europeans began to warm a little to the new and improved Iran during the late 90s, but that ole’ wishy-washy Bill Clinton stuck to his guns and maintained the embargo, even as the Republicans cravenly denied him the chance to govern for a couple of Monica-obsessed years. Inside Iran, a rift was developing between the reformers who supported President Khatami and the conservatives who backed Ayatollah Khamenei. In 1999, severe restrictions were placed on reformist newspapers and media outlets by theocratic decree, which led to pro-democracy demonstrations in Teheran (those fickle college students again) and fundamentalist counter-demonstrations. The conservatives in the government were successful in silencing the reformist press altogether in 2000, despite the reformers having won two-thirds of the seats in that years’ parliamentary elections. Even this new-found power was insufficient to overturn the press restrictions, however, and Khamenei and his clerical councils were able to retain power by appealing to a higher authority than a constitution.

Khatami’s last term in office was dominated by conflicts with the conservative Council of Guardians, which had the ability to bar any candidate it wished from running in elections, and with the western powers, who were busily invading Iraq and getting quite nosy about Iran’s nascent nuclear program. Many in the Iranian government supported the Shiite militias in Iraq, though there were some signs of willingness to work with the international community on the nuclear thing under Khatami.

This spirit of glacial détente evaporated entirely with the parliamentary elections of 2004. Not surprisingly, the emboldened Council of Guardians used its newly-minted authority to pick and choose candidates (calm down, George – it’s not an option here. yet), thus securing two-thirds of the Majles for themselves. Also not surprisingly, the reformers protested that the election had been rigged – there were sitting members of parliament who were barred from running for reelection – and a messy electoral boycott by their disillusioned supporters wound up helping the conservatives, whose voters didn’t stay home.

The hard-liners pushed for a restart of the nuclear program in the summer of 2004, and in so doing rattled some international cages. Issues regarding uranium enrichment in Iran now involve the governments of the United States and Russia (among many others), the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations, the UN Security Council, and the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, and remain as dangerously unresolved today as it was two years ago. The hard-liners solidified their control of the government in 2005, however, with the suspicious election of Teheran’s mayor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (link is to his blog), a fiery conservative veteran of the Imposed War – and quite possibly the Iran Hostage Crisis – whose speeches have proven so provocative that Khamenei in 2005 broadened the presidential oversight powers of the Expediency Council, which was headed by former president (and kinda-reformer) Ali Akbar Rafsanjani.

And since the rest is a little more BREAKING!!! than we historiorantologists generally like to report, the story continues in tomorrow’s newspaper. 😉

Historiorant:

Well, that’s it: What began with an idea to do a pair of 3-page stories on Persia turned into something like 40 pages of single-spaced stuff spread over seven diaries, and I wanted to give a shout out to all those who’ve supported me with comments, ratings, and recommends: Thanks to all those who found these diaries helpful, informative, or funny – it’s been my great pleasure to serve as your court historian on this long journey, and for the past 2+ years. This was the series that started me on the blogging path – the next one, which began in April, 2006, was on the Crusades, and next week’s historiorant will pick up with a really cool (imho, anyway) update on the way that one’s going to be re-published.

Before we get to that, though, I’d like to mention a few things that I learned in completing both the original version of this series, and its modern update. In doing the research for these pieces, I have come to know, albeit in a small way, a culture so ancient, so worthy of pride, that to use those very terms to describe it seems trite. If one thing seems clear about the history of Iran, it is this: this is a land of passionate extremes, a land whose people carry an independence-minded streak that goes clear back to the satraps who followed Alexander’s successor Seleucus. Today’s Iran is not the theocratic Shi’a reign of the early Safavids, but this is the country that gave us the Safavid dynasty. It is also the land that provided the administrators of the Abbasid Empire and an economic system to the entire Islamic caliphate, and home of the horse archers that stopped the mighty Romans in a sky-darkening cloud of merciless arrows. Its rulers have at times controlled vast swaths of the earth; its inhabitants have exerted a force on world culture that extends further still.

America tends not to do well when we attack nations with whose history we are unfamiliar. In both Korea and Vietnam, and now in Iraq, those over whom we would rule found a wellspring of stubbornness in their long, fluctuating histories of golden ages, conquest, defeat, and development. Those who would lead us into war with Iran – Persia, land of Cyrus the Great – would be well advised to remember that.

History for Kossacks: The Persia Series

History for Kossacks: Ancient Persia

History for Kossacks: Classical Persia

History for Kossacks: Islam Comes to Persia

History for Kossacks: Medieval Persia

History for Kossacks: Sufis, poets, a messiah, and a dead parrot – guest-rant from klizard

History for Kossacks: Persia and the Great Game

History for Kossacks: The Shahs of Iran

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Never In Our Names, Bits of News, Progressive Historians, and DocuDharma.

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

I think my next challenge will be to figure out how to work borders and stuff…

either way, sir, I respect your writing very much, and my question is:

After 9/11, the Iranian government offered to help us fight terrorism, and our moronic government refused them. In fact, El Chimpo completely blew them off, IIRC.

Now Chimpy and the Evil Sidekick want to wage a (_nother_) war against a nation that could/should have been our ally

What do you think we, as citizns of this (formerly) free nation can do to de-fang our own incipient authoritarian politicos, especially given today’s NYTimes expose of their psyops being used against us?

I really do not know what to say except this essay takes blogging to a new standard

tx`

u.m., this is brilliant stuff. thanks so much for your hard work! i’ve previously enjoyed reading your essays on dkos, glad to see you here too.

And get Kees van der Pijl’s new book “Nomads, Empires, States” if you can… very enlightening…

UM. Thank you for taking the time to do it.