Greetings, literature loving Dharmosets (or whatever)! Earlier this week, the venerable Moonbat wove a history of ancient Mesopotamia, of Sumeria and Akkadia and Babylonia, of kings and tyrants. Today it is my daunting challenge to supplement his essay with a close reading of Gilgamesh, the semi-fictional account of a Sumerian king on a mad quest for immortality.

Greetings, literature loving Dharmosets (or whatever)! Earlier this week, the venerable Moonbat wove a history of ancient Mesopotamia, of Sumeria and Akkadia and Babylonia, of kings and tyrants. Today it is my daunting challenge to supplement his essay with a close reading of Gilgamesh, the semi-fictional account of a Sumerian king on a mad quest for immortality.

If you haven’t read Moonbat’s excellent introduction to the history of ancient Sumeria – drop what you’re doing and read it now! Then you’ll be ready to wrestle with the ancient man-god-king before he drags us to the edge of the world in search of eternal life. Along the way we’ll meet goddesses and giants, scorpion-beasts and feral men, and we’ll learn about life before the Great Flood…

The friend I loved has turned to clay. Enkidu, the friend I love, has turned to clay.

Me, shall I not lie down like him,

never again to move? (X.ii.12-14)

Gilgamesh is the earliest surviving piece of “big” literature: that is, something more substantial than maxims, law codes, hymns or inscriptions. Its main topic is death, its main thesis is the inevitability of death, and it fittingly almost didn’t survive into the contemporary world.

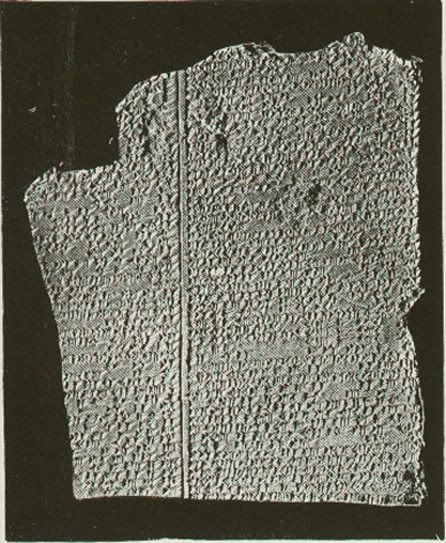

Luckily, the first Gilgamesh tablets were discovered in the mid 19th century by Englishman Austen Henry Layard, whose bestselling accounts of his excavations of Nineveh and Nimrod are full of all the derring-do (and dated cultural views) you’d expect from a 19th century imperialist/adventurer. The importance of the fragments wasn’t realized until 1872, when translator George Smith realized he was working on an elaborate account of the Great Flood – but a decidedly non-Biblical one.

Suddenly interest surged, and over the last hundred years more and more fragments related to the great Sumerian king have been unearthed. We now know that the historical Gilgamesh, son of the previous king Lugulbanda and allegedly of the goddess Ninsun, ruled the city of Uruk in the first half of the third millennium b.c.e. The earliest surviving accounts of his exploits comes from late Sumeria (around 2000 b.c.e.), and the version most often used in modern translations is the Akkadian compilation by Sin-leqi-unninni.

Suddenly interest surged, and over the last hundred years more and more fragments related to the great Sumerian king have been unearthed. We now know that the historical Gilgamesh, son of the previous king Lugulbanda and allegedly of the goddess Ninsun, ruled the city of Uruk in the first half of the third millennium b.c.e. The earliest surviving accounts of his exploits comes from late Sumeria (around 2000 b.c.e.), and the version most often used in modern translations is the Akkadian compilation by Sin-leqi-unninni.

Note that this was already a compilation: there is no “epic” of Gilgamesh per se, so I join with scholar John Maier in calling it simply Gilgamesh. Various versions floated around, and even the most complete are lacking entire episodes, or have sections so badly damaged by time that they are unreadable. Nevertheless we can consider the Sin-leqi-unninni version a complete text, because he (or someone before him) had given the story a framework that unites the beginning and ending into a satisfying thematic whole.

—> A brief note on textology (feel free to skip if this isn’t your bag): there are many translations of many versions of Gilgamesh, and the one I’m using for this diary is neither the most recent nor the most accurate. Advance apologies, but I have two versions on my shelf already and no time to dig through the musty library shelves to compare. Fortunately one of my two versions is the outstanding 1980s version which John Gardner was working on before his tragic death – it’s that version I’ll be using for this essay, even if more recent scholarship has overturned or corrected some of its conclusions. The general points are still, to my knowledge, accepted. I will not be including the controversial 12th tablet in this discussion.

This diary will be a bit different than my usual Literature for Kossacks spiel: it’s much more difficult to extract themes from Gilgamesh without discussing the very plot-heavy narrative, so I’ll be doing a complete summary of the plot instead, picking apart themes as we come across them. This one’s a doozy, and I apologize for the length! But Gilgamesh is worth every minute: it’s the text that convinced me to study literature as a career.

So let’s begin:

šá nagba imuru: the one who saw the abyss

The one who saw the abyss I will make the land know;

of him who knew all, let me tell the whole story. (I.i.1-2)

Right away the two most important themes of Gilgamesh are laid at our feet: knowledge and preservation of that knowledge. Whether this prologue was part of the original Gilgamesh tales or a later interpolation, by the time of Sin-leqi-unninni’s compilation the value of recorded history and information was foregrounded in the text. Gilgamesh will not be just an string of adventures but a revealing of previously hidden knowledge, preserved for future generations.

This is the first of Gilgamesh’s great accomplishments: the second is the fortification of Uruk. Note that, despite Gilgamesh’s reputation as a warrior king who toppled giants, the walls of Uruk are the true testimony of his greatness. In a moment of meta, the author reaches out to the reader for verification:

Ascend the walls of Uruk, walk around the top,

inspect the base, view the brickwork.

Is not the very core made of oven-fired brick?

As for its foundation, was it not laid down by the seven sages?

One part is city, one part orchard, and one part claypits.

Three parts including the claypits make up Uruk. (I.i.16-21)

After this brief prologue the story begins in medias res: the great king Gilgamesh, who is two-thirds god and one-third man, has already become a tyrant. The people cry out to the gods over their king’s harsh demands, which may have included forcing young women to grant him jus primae noctis.

In response, the gods decide to create a rival for Gilgamesh: a wild human with superhuman strength to compete with the tyrannical king. The goddess Aruru creates the rival from clay and throws him into the wilderness, where he runs with gazelles and lives ferally.

Now the narrative shifts to this hirsute wanderer, Enkidu the fighter. When a hunter (the Stalker) meets him by chance at a watering hole, he asks his father how to deal with the Wild Man – his father, like any good parent, suggests sex. Gilgamesh allows them to summon a temple priestess/prostitute (the vocation wasn’t so reviled as the English word suggests) who seduces Enkidu in a marathon bout of fornication: six days and seven nights!

—> Some scholars read the taming of Enkidu as an allegory for the process of civilization: as Orson Welles once said, “We made civilization in order to impress our girlfriends.” Whether this reading is legit is hard to say: we’re working with fragments of fragments about a culture we barely understand. The Sin-leqi-unninni version is badly damaged in this section, but other versions of the story have the woman teaching Enkidu all about the civilized world: how to eat cooked food and drink wine, to wear clothes and to bathe, etc.

Post-coitum, Enkidu finds he can no longer return to the animals, who now distrust the deflowered fighter. He shifts his attention to the world of human beings, and when he hears their complaints of Gilgamesh’s cruelty, he’s ready for the challenge…

The Ancient Buddy Movie

The great king and the wild fighter duke it out, but like two boys in a schoolyard the tumbling in the dust turns them into close friends rather than blood enemies. Gilgamesh and Enkidu are fated not to be rivals, but something far deeper. In his dreams before the fight, Gilgamesh sees Enkidu as one he will “hug like a wife” (in Sandars’ translation, “his attraction was like the love of a woman”: the sexual connotation is emphasized by the fact that both are described to each other through their sexual prowess:

Gaze at [Gilgamesh] – observe his face –

beautiful in manhood, well-hung,

his whole body filled with sexual glow. (I.v.15-17)

—> We should always be wary of applying 21st century notions of sexuality to ancient cultures we barely understand, but the strong bonds and sexualized nature of the discourse here have definitely led to discussions about the physical extent of Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s relationship. As far as the text is concerned, they were joined at the hip – whether literally or metaphorically is purely conjecture (see the links below for more info on this point).

Once their friendship is sealed, the heroes need deeds to make their names: first comes the battle with the giant Humbaba, who guards the cedar forests to the north. The text is fragmentary, but a few points are clear: Humbaba is called “evil” (for whatever reason), the god of justice Shamash aids the heroes in defeating him, and the whole thing may be an elaborate allegory for the spread of Sumeria into the north, where the necessary cedar for building was located. Witness the birth of ecological imperialism!

But Gilgamesh’s success wins him a dangerous admirer: the goddess Ishtar. Like many goddesses of love in antiquity, she was known for seducing mortals and leaving them to unfortunate fates – Gilgamesh is not so foolish to fall for her feminine wiles:

But Gilgamesh’s success wins him a dangerous admirer: the goddess Ishtar. Like many goddesses of love in antiquity, she was known for seducing mortals and leaving them to unfortunate fates – Gilgamesh is not so foolish to fall for her feminine wiles:

Which of your lovers have you loved forever?

Which of your little shepherds has continued to please you?

Come, let me name your lovers for you. (VI.i.42-44)

Which he then proceeds to do. Furious, Ishtar demands that her father, the god Anu, send a ferocious heavenly bull to attack Gilgamesh. Which he then proceeds to do. Unfortunately the powerful king and his superhuman buddy dispatch of the bull in a feat of acrobatic strength, and Ishtar angrily shouts:

“Curse Gilgamesh, who has besmeared me, killing the Bull of Heaven!”

When Enkidu heard this, the words of Ishtar,

he tore out the thigh of the bull and threw it in her face. (VI.v.159-161)

You know this won’t end well.

Mortality

Insulted and injured, Ishtar demands justice from the gods: they are unwilling to hand over their favorite son Gilgamesh, so the verdict falls on the shoulders of his sidekick. Soon Enkidu falls sleep and has a feverish vision of the afterlife – one of the most stunning passages in Gilgamesh, a detailed description of the gloomy destiny that awaits us all:

He seized me and led me down to the house of darkness, house of Irkalla,

the house where one who goes in never comes out again…

the place where they live on dust, their food is mud;

their clothes are like birds’ clothes, a garment of wings,

and they see no light, living in blackness. (VII.iv.33-4,37-8)

Most striking about Enkidu’s vision is the lack of judgment of any sort: all the dead find themselves in the same despairing fate, whether powerful or weak, good or evil.

Unfortunately for Enkidu, this is no vision: his body is soon racked with fever and he expires. Gilgamesh is devastated, and his lament is among the most beautiful passages in the entire work:

For Enkidu, for me friend, I weep like a wailing woman,

howling bitterly.

[He was] the axe at my side, the bow at my arm,

the dagger in my belt, the shield in front of me,

my festive garment, my splended attire… (VII.ii.2-5)

Enkidu’s death begins the second half of Gilgamesh: the mad quest of a king who has suddenly learned the meaning of mortality and is in a race against time to protect against his own. Gilgamesh may be part-god, but the human part will not live forever.

But Gilgamesh knows of one man who beat the system: the immortal Utnapishtim, who lives immeasurably far away, beyond the mountain of night. Though the geography of the narrative has so far been (mostly) realistic, the quest becomes a surreal trip through fantastic landscapes, with Scorpion people in mountain passes, a void of total darkness that takes days to cross, an Edenic paradise, and a mysterious and deadly river that requires stone creatures to cross. At every stop he is warned that his journey is futile, and that he would do better to return home.

The void of total darkness is one of the most fascinating parts of the text: exact repetitions underscore the brutality of Gilgamesh’s journey, which no human being has ever undertaken:

When he had gone seven double-hours,

thick is the darkness, there is no light;

he can see neither behind him nor ahead of him.When he had gone eight double-hours… heat flares up in him;

thick is the darkness, there is no light;

he can see neither behind him nor ahead of him.When he had gone nine double-hours… the north wind [bit into] his face:

thick is the darkness, there is no light;

he can see neither behind him nor ahead of him. (IX.v.32-40)

Et cetera.

On the last leg Gilgamesh meets Urshanabi, the boatman who will take him across the waters of death, and who will also become his traveling companion for the rest of the tale.

Flood and Failure

The end point of Gilgamesh’s fantastic quest is the home of Utnapishtim – “the remote one about whom they tell tales” – who alone (with his wife) has been granted eternal life. Utnapishtim explains to the king that his immortality was a special case: he survived the Flood.

Many generations before, the gods had decided to eliminate life on earth – for reasons that are not well-explained in the surviving tablets. Wanting someone to survive but unable to reveal directly what the other gods are planning, the god Ea whispers the plans to the reed walls of Utnapishtim’s hut – hey, it’s not his fault if someone overhears him! But how to make a strong enough boat without the rest of town growing suspicious? Ea gives Utnapishtim a punning speech to deliver in case anyone asks:

Many generations before, the gods had decided to eliminate life on earth – for reasons that are not well-explained in the surviving tablets. Wanting someone to survive but unable to reveal directly what the other gods are planning, the god Ea whispers the plans to the reed walls of Utnapishtim’s hut – hey, it’s not his fault if someone overhears him! But how to make a strong enough boat without the rest of town growing suspicious? Ea gives Utnapishtim a punning speech to deliver in case anyone asks:

[The god Enlil] will make richness rain down on you –

the choicest birds, the rarest fish.

The land will have its fill of harvest riches.

At dawn bread

he will pour down on you – showers of wheat. (XI.i.43-47)

The word “bread” (kukku) is pretty close to the word “darkness” (kukkû), just as the word “wheat” can also mean “misfortune” (kibtu). The townspeople hear what they want to hear, and Utnapishtim goes about his work with a clear conscience. Like the Biblical Noah, he builds an ark of titanic dimensions, seals himself in with his family and a smattering of terrestrial animals, and waits out the deluge.

—> The description of the Flood of Gilgamesh is longer and more detailed than the one in Genesis, and deserves a much closer reading than I can give it here: here’s the full text for your own perusal. Despite some pretty obvious overlap, it’s unlikely that either story was the inspiration for the other, but that both grow out of a common, archetypical tradition.

But there was only one Flood, so Utnapishtim’s gift of immortality will not be repeated. Still, Gilgamesh has one chance left: a magic plant that grows at the bottom of the sea. The king retrieves it, only to watch it moments later devoured by a snake (who, in a moment of subtle pourquoi, sheds its skin). Gilgamesh collapses into tears at the ultimate failure of his quest: he will die.

Gilgamesh has failed, but his failure is the eternal failure of mankind to avoid our fates. Death comes for us all, even those who are two-thirds god. No wonder early translators considered this text the ultimate in pessimistic epic-making.

But has Gilgamesh really failed in his quest for immortality? The closing lines of the story give us reason to hope. Returning home to Uruk, Gilgamesh recognizes that his name will live forever, even when his body passes away – and with this closing challenge to Urshanabi, Gilgamesh becomes a work of almost transcendent power:

Gilgamesh said to him, to Urshanabi, the Boatman,

“Go up, Urshanabi, onto the walls of Uruk.

Inspect the base, view the brickwork.

Is not the very core made of oven-fired brick?

Did not the seven sages lay down its foundation?In [Uruk], house of Isthar, one part is city, one part orchards,

and one part claypits.

Three parts including the claypits make up Uruk.” (XI.vi.303-307)

An extremely sophisticated ending: the text collapses Gilgamesh with the narrator – the storyteller is the king. The reader has returned to the beginning, and the walls of Uruk stand as an unchanging testament to the king’s greatness.

Gilgamesh too has returned, armed not only with the knowledge of life before the Flood, but also with a new maturity and understanding of the importance of his accomplishments. He will die, but the walls of Uruk, the story of the flood, and Gilgamesh itself are immortal.

If that sounds like cold comfort, consider this: here we are nearly 5000 years later, and we’re still talking about him.

Links

- A full translation online by Maureen Gallery Kovacs

- An online review of Susan Ackerman’s work on sexuality in ancient culture, When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David

- Links to various Gilgamesh-related texts from ancient Babylonian culture

- Online essay by Arthur Brown: “Storytelling, the Meaning of Life, and The Epic of Gilgamesh“

All quotations from the John Gardner/John Maier Gilgamesh, published by Vintage Books. All images from Wikimedia commons, linked back to their source pages

A special thanks to Unitary Moonbat for agreeing to do this 2-part series: and please read part one if you haven’t already. Thank you for reading!

8 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

I’ll be out of town, so it depends on what I can raid from my brother’s bookshelves.

Suggestions for future installments?

Thanks for this detour down memory lane.

I am trying to do too many things at once!

But Gilgamesh fascinates me….just for the ancientyness.

Plus the fact that clay tablets are our first written medium….and they survived!

Thanks Pic!

–Jean Luc Picard, Darmok