Greetings, literature-loving dharmosets! Last week the series had a guest poster who tackled a close reading of one of Edith Wharton’s best known works, The House of Mirth. This week we’re going to crawl into the WayWayback machine to address one of history’s most baffling short stories.

Why do people suffer? If there is a God, and he does have a ‘plan’, why do people who believe in him find themselves suffering the same indignities as people who don’t?

I have no interest in the religious side of this question (I’m an atheist), but the it makes for fascinating art. If you think religious texts aren’t appropriate fodder for literary analysis… well, then this ain’t the essay for you!

Otherwise, join me below for a trip through ancient Edom.

“I read the Book of Job last night – I don’t think God comes well out of it.”

— Virginia Woolf

The world’s religions have no shortage of parables, poems, fables, histories, and biographies, so why should we bother with Job, a relatively minor piece (in dogmatic terms) of obscure cultural origin? The plot is relatively straightforward, if confusing and uneven; the poetry is good but you can certainly find better; and no one can seem to agree on what it was intended to mean.

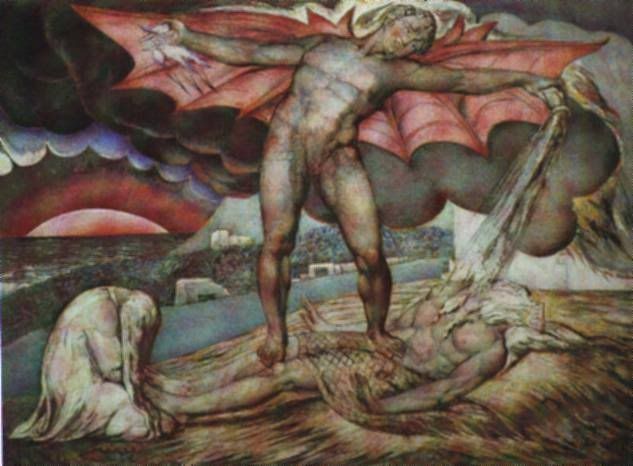

Yet no book of Jewish scripture (for that matter, no book of the Bible) has inspired such a wide array of admirers and analysts, including psychoanalyst Carl Jung, playwright Neil Simon, philosopher Lev Shestov, pundit William Safire (generally ugh, although his reading is interesting)… enough people to merit a three volume study of Job’s impact that includes Hobbes, Spinoza, Pascal, Voltaire, Goethe, Blake, Kierkegaard, Melville, Dostoevsky, and Camus. Notice this list includes a span from conservative Christians to atheists.

I have my own theories why, but first let’s back up and discuss the history of this disjointed text, and how it came to achieve such a high place in Western thought.

On Edomites and Textology

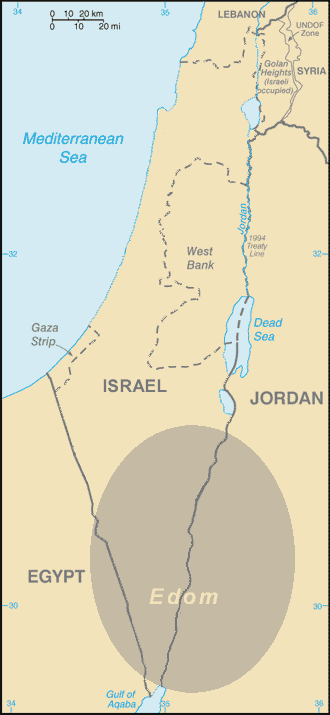

Scholars aren’t 100% sure where Job originates, but one thing is fairly certain: neither the story nor its central character is Jewish, which makes its inclusion in the Jewish scripture an interesting choice. The present form of the story describes Job as an Edomite, living in a kingdom located roughly on the border of southern Israel and Jordan.

Scholars aren’t 100% sure where Job originates, but one thing is fairly certain: neither the story nor its central character is Jewish, which makes its inclusion in the Jewish scripture an interesting choice. The present form of the story describes Job as an Edomite, living in a kingdom located roughly on the border of southern Israel and Jordan.

According to tradition, “Edom” derives from Esau, the older brother of Jewish patriarch Jacob (much as Arabs are traditionally linked to the older brother of Jewish patriarch Isaac). The archaeological record is unfortunately scant.

As for the text itself, it’s undergone significant meddling between its likely origins as an oral tradition and its modern form. For one thing, we’re fairly certain that an enterprising scholar (or community of scholars) felt that the bare story of Job was too unclear theologically, so they added a new character and possibly rewrote some of the lines. How we know this will become clear when we discuss the plot.

Oddly enough, these “clarifications” backfired: Job is still a baffling piece of literature, and the contradictions and discomforts stem in part from the sections added as “clarifications”. It’s as if, attempting to simply a text for general readership, the scholars created a Frankenstein’s monster of terrible depth.

On Boils and Potsherds

Job is the great work of Suffering, and its pages have been dogeared by a hundred generation of readers trying to understand why bad things happen. Here’s the plot in a nutshell:

To prove a point, God allows one of his most upstanding people to be the target of some seriously brutal suffering. Job (the target) knows he’s done nothing wrong and cries out to heaven for justification. Eventually God comes down in a whirlwind, tells Job to shut up, and rewards him for passing the test.

Got that? It’s simple enough (if baffling) on the surface, but as with many texts of this depth the devil is in the details.

Literally: the plot is set in motion by none other than Satan, in his very first appearance as a literary entity. But the word “Satan” actually means “Accuser”, and whoever he is, he’s not a fallen angel or proprietor of the hottest property this side of the Sahara. As far as the story is concerned, Satan is God’s prosecutor, testing the abilities of the human race to “fear God and shun evil.” The trials of Job start off as a glorified bet:

Then the LORD said to Satan, “Have you considered my servant Job? There is no one on earth like him; he is blameless and upright, a man who fears God and shuns evil.”

“Does Job fear God for nothing?” Satan replied. “Have you not put a hedge around him and his household and everything he has? You have blessed the work of his hands, so that his flocks and herds are spread throughout the land. But stretch out your hand and strike everything he has, and he will surely curse you to your face.”

The LORD said to Satan, “Very well, then, everything he has is in your hands, but on the man himself do not lay a finger.” (1:8-12)

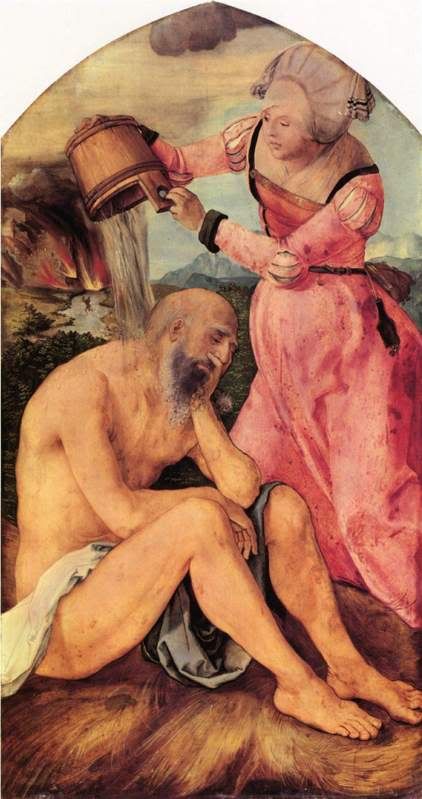

With those words, Job’s formerly happy existence becomes a living hell. His property is stolen or destroyed, all his children are killed in freak accident of nature, and – after God wants to declare victory, but Satan ups the ante – his body becomes infected with oozing, itchy boils.

With those words, Job’s formerly happy existence becomes a living hell. His property is stolen or destroyed, all his children are killed in freak accident of nature, and – after God wants to declare victory, but Satan ups the ante – his body becomes infected with oozing, itchy boils.

Now the story really begins: the plot shifts away from this prose prologue into an elegant poetic structure, as Job’s three friends try to convince him about how to deal with his misfortunes.

Job curses his miserable existence, but his friends have other ideas. Eliphaz believes that God makes no mistakes, and good people are rewarded for good just as bad people are condemned. Job isn’t amused, and you can practically hear his anger seething out between clenched teeth:

I will not keep silent;

I will speak out in the anguish of my spirit,

I will complain in the bitterness of my soul.

…If I have sinned, what have I done to you,

O watcher of men?

Why have you made me your target?

Have I become a burden to you? (7:11, 20)

Friend #2, Bildad, replies with more of the same, arguing that God’s actions are just by nature. He couches his argument in some pretty, imagery-laden verse, but beneath the poetic platitudes he’s implying that Job has to repent, because obviously he’s done something wrong to merit all this catastrophe. Job’s bitterness pours out in response:

It is all the same; that is why I say,

‘He destroys both the blameless and the wicked.’When a scourge brings sudden death,

he mocks the despair of the innocent.When a land falls into the hands of the wicked,

he blindfolds its judges.

If it is not he, then who is it? (9:22-24)

Friend #3, Zophar, has none of the tact of the other interlocutors, and blasts Job for his arrogance in assuming he’d done nothing wrong. Now the text settles into its pattern, as the friends continue, in order, to berate Job for his wrongheadedness while Job proclaims his innocence and the unfairness of his suffering.

First Eliphaz, then Bildad, then Zophar,

then Eliphaz, then Bildad, then Zophar,

then Elipahz, then Bildad, then Elihu.. wha?

Who the hell is Elihu?

We’re 32 chapters in, and a previously unmentioned character has decided to butt into the conversation – with a prose prologue to introduce him in a slipshod, unconvincing way (“He was there all along, really! He just didn’t like talking over the other people!”) The newbie, whose name means “My God is He” – how’s that for subtle? – starts ripping into everyone, Job and friends alike, for not understanding the nature of divine justice. Job doesn’t have to repent for anything – he simply has to recognize that understanding divine justice is so far out of his cognitive abilities that he shouldn’t presume to know better.

As if on cue, God enters stage left, in a whirwind (heck of an entrance!) Rather than argue with Job about the rightness or wrongness of his punishment, God puts their relationship into some perspective:

Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation?

Tell me, if you understand…Who shut up the sea behind doors

when it burst forth from the womb? (38:4, 8)

And then God invents snark:

Surely you know, for you were already born!

You have lived so many years! (38:21)

And with that, trembling at the mighty boom from the whirlwind, Job accepts his fate. God says, “I win!” and gives Job everything back, including a new set of children and blemish-free skin. Finita la commedia

Exegesis

I’m troubled, I’m puzzled, I have more questions than answers-and that, I suppose, is why the Book of Job has been required reading for almost 3,000 years.

— David Plotz, Slate

There are so many directions we can go with this text – if it’s been rich enough to inspire thousands upon thousands of pages of discussion through the centuries, I certainly can’t but scratch the surface in a blog post. Some areas of particular interest:

Sin and Punishment: One of the radical things about Job is that it disconnects the notion of earthly misfortune from sin. Depending on how you approach it, this is either extremely discomforting (the world around us follows no understandable logic, and we’re all randomly-squashed ants!) or extremely comforting (a natural catastrophe that takes the lives of thousands of people is not anyone’s fault, so fuckwads like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson can shove it). Besides, why should the Almighty care about earthly peccadilloes that barely register? On the flip side of the coin, you didn’t get that promotion because you prayed, and you didn’t find your keys because you’re “a good person”. As Elihu explains,

Sin and Punishment: One of the radical things about Job is that it disconnects the notion of earthly misfortune from sin. Depending on how you approach it, this is either extremely discomforting (the world around us follows no understandable logic, and we’re all randomly-squashed ants!) or extremely comforting (a natural catastrophe that takes the lives of thousands of people is not anyone’s fault, so fuckwads like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson can shove it). Besides, why should the Almighty care about earthly peccadilloes that barely register? On the flip side of the coin, you didn’t get that promotion because you prayed, and you didn’t find your keys because you’re “a good person”. As Elihu explains,

If you sin, how does that affect him?

If your sins are many, what does that do to him?If you are righteous, what do you give to him,

or what does he receive from your hand? (35:6-7)

Language: more so than any Biblical text outside of Genesis, Job concerns itself with the role and function of language. Apart from the framing device, the book is almost entirely dialogue, foregrounding conversation and speech above an action-less plot. When God finally appears, it’s in the form of a disembodied voice.

But it recognizes itself as a literary text, too. In a nice moment of ancient Meta, Job hopes that future generations will recognize him for the blameless soul that he is:

Oh, that my words were recorded,

that they were written on a scroll,that they were inscribed with an iron tool on lead,

or engraved in rock forever! (19:23-24)

This eventually leads to one of the text’s most interesting paradoxes: if the moral of the story is that divine justice is beyond our understanding, surely it must be beyond our language, too. This is doubly true since language, even in the Bible, is considered a corruption – or an inferior form of human understanding. How does the book deal with this?

The Sublime: The limitations of language are in part a reason for God’s non-response response. If divine justice were explainable, he’d explain it; but it isn’t, so he doesn’t. Instead, God relies on imagery – giant oceanic Behemoths, creation of the cosmos, booming whirlwinds – to carry a sense of what Job is dealing with.

Basically, Job has a meltdown. Faced with the enormity of creation thrust in front of him, his neurons overload and he reaches a better understanding of the enormity of the Ineffable. Kant called this type of meltdown “the Sublime” and recognized that it could lead to the annihilation of a sense of self in the face of the Absolute.

The Sublime, of another sort: Why does this text inspire so many contradictory responses? Part of the reason is that the theology (or more accurately, the theodicy) is so unsatisfying, and it has to be: as we just noted, if it were explainable, it could be explained. And yet it all starts with a bet – in fact, the text explains to us exactly why Job is suffering, then berates Job for trying to understand the nature of his suffering! Satan shows us his cards, Elihu tells us we can’t see the cards. What gives?

Punishment that is not punishment, justice that is not justice, an explanation that is not an explanation. Job loops back on itself with visions of a universe outside our understanding while seeking to make it understandable, and the more you contemplate its mysteries, the more you find yourself sinking into incomprehension. In the end, faced with such an agonizing push-and-pull of ideas, your brain suffers a meltdown.

A-ha.

It’s just my reading, but I think this is the source of Job‘s greatness: its inscrutable nature forces the reader to reenact Job’s own meltdown when faced with the divine. Since the text can’t deliver a whirlwind to each of our homes, it creates a cognitive whirlwind by beating us up with an incomprehensible theodicy, and we’re left cowering in the corner. But as with Job, this also precipitates our breakthrough in understanding the Ineffable on a higher level.

And even if you find that you don’t get quite the same uneasy feeling reading the book, you can still enjoy one major aspect: at its center stands the best-written, most vivid character in all Jewish scripture. Job appeals to readers because he is so recognizably human, and his suffering and his indignation still feel potent some thousands of years later.

My eyes have seen all this,

my ears have heard and understood it.What you know, I also know;

I am not inferior to you. (13:1-2)

Links:

– New International version of Job, which is the version I used for this essay

– Fully illustrated Job by William Blake (a must-see!)

– Excellent essay by Slate’s David Plotz in Blogging the Bible (and a much better close reading than I’ve written here)

– Essay on Job by G. K. Chesterton (early 20th century author of popular novels like The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare)

– Putting God on Trial, a comprehensive website on Job by the author Robert Sutherland

Thank you for reading!

Text of Job from the New International translation, linked above. All images courtesy Wikimedia Commons, with images hyperlinked to their original sources. Cross-posted as always on Progressive Historians and Daily Kos.

38 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

Is there a more ridiculous phrase in our culture than “the patience of Job“? This is after all the Job who wails,

Fact is, Job isn’t so much ‘patient’ as ‘pretty fucking upset’. So why do we laud him for a dubious notion of patience that isn’t reflected in his passionate, angry language?

Well, the phrase actually comes from another part of the Christian Bible, the Epistle of James. Here’s the relevant line, King James version:

I’ve not read the original Greek, but likely as not the King James makes up in poetry what it lacks in accuracy. For comparison’s sake, here’s the New American Standard edition:

Now that makes sense: Job may be upset, but he certainly endures. Nevertheless, the powerful language of the King James version is impossible to escape, and all logic to the contrary, Job’s ‘patience’ has become proverbial.

+++++

Otherwise, next week we’ll continue our discussion of meaningful incomprehension with contemporary Japan’s leading pseudo-surrealist novelist, Haruki Murakami. See you then!

is one of the best arguments against love for the Judeo-Christian deity that I have ever read. God inflicts elaborate sufferings on one of his beloved friends, basically on a bet. This is not the sort of deity who deserves love. Terror, distrust, feeble attempts at mollification, sure. But never love.

that it is only a parable, and is not fact, in the same way that rain for ’40 days and 40 nights’ is simply evidence of a lot of rain.

I wasn’t at the council that decided which books would be included in the bible or not, but there are more scholarly arguments concerning whether this is about the expanse of a deity’s power than on the sufferings of one person.

As a parable, it says one thing… but the interpretation through the years has been interesting, especially since there are so many differing ones.

religious text as fodder for literary analysis.

But can’t comment without getting into religion….and what’s the point talking religion with a godless atheist who is going to burn forever in the pits of hell anyway?

REALLY good piece!

Only one correction….God didn’t invent snark, snark invented god.

Great piece–Do I get 3 credits if I pass the final?

Job reminds me of 9/11–why did so many innocents die a horrible death? A rabbi that week said God doesn’t micromanage. Somehow, this pissed me off–as does the book of Job.

While the book “Misquoting Jesus” was obviously referring to the New Testament, after I read “MJ”, I couldn’t help wondering about much of the Old Testament as well.

For those who may not know, Ehrman was an evangelical Christian at a very young age. He went on to become a New Testament Scholar, receiving his Ph.D from Princeton Theological Seminary. No Liberty University for this guy.

Anyhoo, he became quite interested in the earliest known texts of the Bible because he was taught at a very young age, as a Bible Literalist, that it’s The Word of God. If that’s so, he wanted to find the most original word of God.

Along the way, let’s just say he became much, much less devout. He’s now Chairman of the Religious Studies Department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The premise of “Misquoting Jesus” is – and there are two main ones, I think: 1) Since scribes hand-copied these texts for thousands of years errors were made and 2) Some of the “errors” were very much intentional.

For example, I’m sure just about everyone remembers the old parable where the woman is about to be stoned to death by the angry mob for adultery. (I guess the guy got off scott free.) Jesus is hanging out, nearby, drawing something in the dirt with a stick, if I recall. Anyway, and I gotta admit this is pretty cool, he says of course “He among you who is without sin cast the first stone”. (Or close enough…)

Now as I said, that’s a pretty powerful lesson: We shouldn’t judge people for being imperfect when we are imperfect ourselves – let alone kill them. What a great story!

Trouble is, as Ehrman points out, it’s in none of the “original” texts of the Bible. None of the texts are “original” of course. But that parable appears long after the earliest known texts of the New Testament existed.

In other words it was just added along the way by some dude. (Doubt it was a chick; they totally get screwed in The Bible, no pun intended. Women weren’t even allowed in many churches way-back when)

Even if you don’t buy into what Ehrman writes he brings up some fascinating points.

For example literacy was extremely rare a thousand years ago (and the Old Testament is so much older!). Someone who could read and write was *very* valuable to a community to draw up legal, business documents, wills, etc. Over ninety-nine percent of most any given population was illiterate and The Bible was mostly *read to people*.

Obviously no printing press existed so each copy of the Bible for almost two thousand years was hand copied by a scribe.

I know it’s hard for us bloggers to believe this but people actually had political motivations for injecting things they felt would help their position or omitting things they felt may hurt, when reading as well as copying the texts of the Bible.

Anyway, after reading his book, every time I encounter Biblical quotes I think about this. What are the oldest copies we have of The Book of Job for example. Do they jive with the next-to-oldest? Any discrepancies? I just can’t help it.

Ehrman also points out that The King James Version of the Bible comes from notoriously un-reliable texts, many of which had Greek origins, if I recall. Great.

I do find it hard to believe that, over the centuries, men did NOT corrupt these texts to fit personal agendas and that copying errors – intentional or not – happened quite a bit along the way.

(They’re doing that today, in fact)

So Pico’s excellent essay tonight once again left me wondering about the true origins of the Book of Job and if they are terrestrial, (and I personally believe they are) what the motive(s) of the author(s) might be.

Incidentally you can find an audio interview with Ehrman by Diane Rehm that aired a couple of years ago here and I’ll leave everyone with a Colbert quote, who, when Ehrman was a guest on his show, referred to agnostics as “atheists without balls”. 😉

er, I mean Buhdy, take away our Rec button? (Or was it SATAN (atan… atan…)???

I did so want to rec this. Am I being punished. WTF did I do?

Damn you, Buhdy! *shakes fist at sky*

isnt it, to look at ‘god’ as a literary character and not a diety. i have to agree with ms. woolf on this one…

… the story of Job fascinating.

First, you gotta wonder about Job’s wife and children — they die, they’re just sort of spear-carriers in the story. God doesn’t care if Satan kills everyone as long as he doesn’t kill Job. That’s a mystery in itself, as is the notion that Job just gets a new wife and children and doesn’t miss the ones that died.

Aside from that, Job, I think, won a great victory. There’s many analogies one can make from this story.

But to me, the one that suits our times the most is the notion that we have to trust in our own understanding, even if that understanding is decried by virtually everyone around us.

All the well meaning friends of Job gave forth believable explanations – and here was Job, all weak and broken – most of us would, if not cave in to those explanations, at least be confused by them enough so we wouldn’t know what to believe.

But not our man Job! In his own enraged way, he has faith, he knows he is not being punished even when all the physical evidence around him says he is. He knows there is another reason and he doesn’t let God off the hook until God himself appears to him. At that point, I don’t think Job cared what God had to say — it was God’s very appearance that confirms to Job he was right – this was not punishment.

Think how one feels, for example, when bad things happen. Is it the misfortune alone that is painful, or the notion we may deserve it, that it is punishment? What if we knew beyond doubt that it was not punishment, that we did nothing wrong? We would still suffer, still perhaps be angry, but the pain and suffering of guilt and confusion would not be there.

I think this is a powerful psychological and spiritual story that has a great deal of resonance to our own times.

“In dust and ashes, I repent.”

Then, he gets back all that he had, and more.

God says: Hint, hint.

I particularly like your conclusion about the textual delivery of inscrutability to the reader.

Kant thought that the (dynamic) sublime–the awesome in nature–completely overwhelmed the imaginative faculty because the sublime has no form, as opposed to the aesthetic object. With the imaginative faculty overwhelmed, reason steps in to save the day… and the majesty of reason replaces the awesomeness of the sublime. You end up admiring the awesomeness of reason, instead of being overwhelmed by the awesomeness of the sublime.

I think, especially given your conclusion, that the text of Job works the same way as salutary reason tempers the sublime, makes understandable what is at first overwhelming.

consider this one hand clapping. if you know what i mean…

haahabwahahahehao.